Mark Dunkelman’s Why Nothing Works is full of so much great history that I needed to do another post on it and pull out some of the juiciest case studies. My original review is here, but I’ll start with a quick reminder of the book’s thesis. Feel free to skip this section if you’ve read my review:

Since the 1960s there has been a well-intentioned progressive impulse to check abuses of centralized government power and protect individual rights, particularly for minorities. This approach has merit, but over time has led to a government hobbled by process and incapable of getting stuff done.

Dunkelman is quick to point out that a powerful, New Deal-style federal government is not more or less progressive than, say, a neighborhood group suing to stop that same government from bulldozing their neighborhood for a freeway. They’re just different approaches to power that have always been in tension with each other.

His argument is that we’ve gone too far in one direction (decentralization, bogging the government down with process) and need to find a better balance between these two approaches. It’s quite similar to Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s idea from Abundance (my review is linked below) that we need to improve state capacity, the government’s ability to implement its policies.

Dunkelman’s historical narrative throughout the book is essentially American politics minus conservatives. He does this to avoid finger pointing and to force progressives to reckon with their role in both the problem and (hopefully) the upcoming solutions.

Part of what’s fun about this historical approach is that it features lots of ironic stories. Unintended consequences and Butterfly Effects reign supreme. I wanted to highlight a few of the more fascinating examples, related to law enforcement, freeways, and environmental law.

Why can’t we fire bad cops?

So much of the post-Ferguson, post-George Floyd racial reckoning moment has been about police brutality. Surprisingly, well-intentioned progressives helped create this situation, where cops can shoot unarmed kids and keep their jobs.

In the 1960s, a wave of Supreme Court decisions attempted to rein in crooked and abusive cops. This is where Miranda rights (“you have the right to remain silent..”) come from, as well as restrictions on using evidence obtained via unconstitutional searches. In this period, police beat up (1968 Chicago DNC) or murdered (Kent State) protestors on national TV. Though I learned in my review of Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland that elites were more upset about this than the general public.

Progressives began to notice a pattern. Low-level cops were often abused and coerced by tyrannical chiefs. Describing Baltimore’s police commissioner Donald Pomerleau, Dunkelman says that the chief “was doing to his rank-and-file what the rank-and-file were precluded from doing to suspected perps.” For example, he disciplined defiant officers by locking them in a “sweatbox” and forcing them to admit to a crime, real or fake.

Pretty bad! It looked like the boss was the real problem and that more liberal beat cops needed to be liberated from tyranny. Therefore, protect them from that pressure and you’d get better cops. A theory very in line with the 1960s focus on “The Man” (evil) vs. regular people (good).

Police unions allied with progressives to enact Law Enforcement Bills of Rights (LEOBORs). It limited the ability of police chiefs to abuse their officers by putting a ton of process around any discipline, including neutral arbitration and confidentiality requirements. Honestly, all pretty normal benefits for a union to prioritize.

Anyone who has paid any attention to politics in the last 10 years knows where this is going:

Decades later, many progressives coming late to the scene would presume that these guardrails were the handiwork of archconservative villains legislators eager to carry water for the police unions in exchange for campaign donations and endorsements.… Arduous due process protections made it impossible, in many cases, to get wayward officers fired from the force. Bad cops appeared free to wreak havoc without repercussion. Racist cops patrolled with impunity. Similarly frustrating, LEOBOR-connected confidentiality provisions prevented chiefs from commenting on accusations of misconduct, giving communities the impression that their complaints were falling on deaf ears-and, in some cases, they certainly were.

We’ve now perversely arrived at a situation with flipped dynamics from the 1960s. Good police chiefs can’t remove bad actors:

In 2021, the City of North Providence, Rhode Island, tried to fire Scott Feeley, a police sergeant charged with a whole rash of violations. He'd been insubordinate to his superiors. He'd lied in the course of an internal affairs investigation. He'd failed to call in traffic stops. In all, Chief Alfredo Ruggiero Jr. brought ninety-seven different charges against him, and the LEOBOR tribunal empaneled to evaluate those charges found him guilty of seventy-nine of them. But the panelists decided, in the end, not to strip him of his badge, as the city demanded. Instead, he was simply demoted to patrolman after serving a forty-five-day suspension. North Providence's mayor, Charles Lombardi, responded in outrage: "What do we do with this guy? He was found guilty of failing to obey, truthfulness.... this is insulting."' And yet there was nothing the mayor could do to keep him off the beat! Feeley returned to service.

The politics of policing have shifted so much over the years. I often think about James Forman, Jr.’s Locking Up Our Own. It’s an excellent book about mass incarceration that shows how literal Civil Rights heroes pushed for more policing and incarceration in their cities, many of them seeing it as the continuation of their groundbreaking movement work from the 1960s. In fact, the lack of law enforcement was evidence of racism to them, a sign that white elites were content to let black communities live in fear of local criminals.

Forman’s argument is pretty nuanced, basically that these figures pushed for more law enforcement and more robust social services and only received the former. But there’s a similar irony with the LEOBORs: the progressive victory comes to look like the work of archconservatives only one or two generations later.

Courts rewriting Congress

The LEOBOR story is one version of the unintended consequences story. The law did ultimately work as intended, but it ended up protecting bad actors. The next two examples show how even modest statutes can get twisted by judicial interpretation into something the original lawmakers never intended. The ultimate impact is the same; what starts as a check on abuse becomes a veto on action.

After the growth of the suburbs, planners rushed to build freeways to make sure that people could still enter and exit the core city freely without choking surface streets with traffic. But where to build these new expressways?

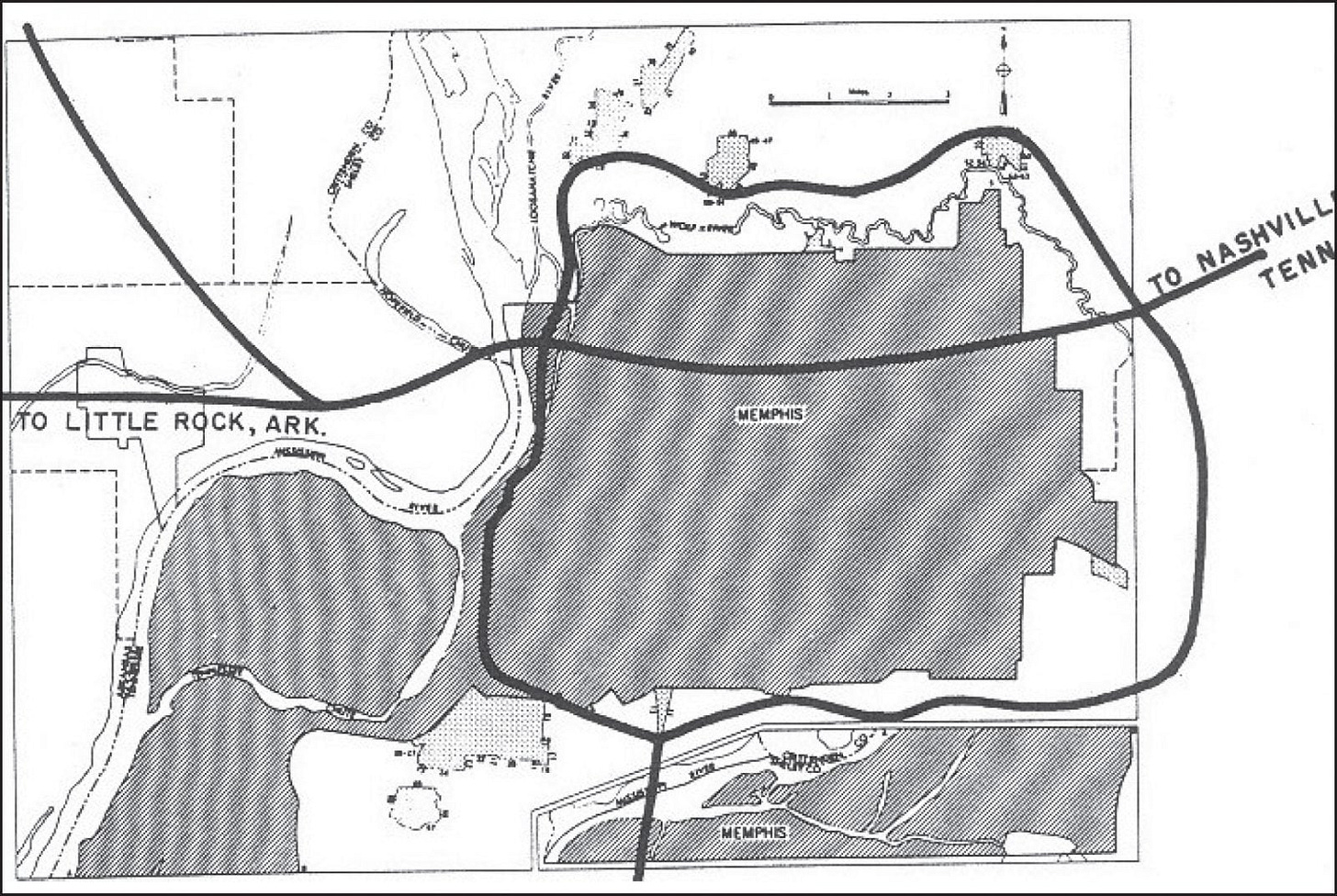

People today often mourn neighborhoods destroyed by freeways. In San Antonio and Memphis, they tried to avoid this outcome and instead build through pieces of large parks. For example, “in Memphis spoiling 26 of Overton Park’s 342 acres would save at least six hundred homes and twenty businesses.” In both cities, this kind of plan passed through local votes, but met opposition.

Those opposed eventually got in the ear of Texas Senator Ralph Yarborough, who inserted some important language into a 1966 bill that established the federal Department of Transportation:

It said, quite simply, that funding issued by the new Department of Transportation could not be used in ways that disrupted public greenery “unless (1) there is no feasible or prudent alternative to the use of the land, and (2) such programs include all possible planning to minimize harm.”

But the Senate was careful to limit the impact of this, making it clear in a separate report that this language was not “a mandatory prohibition against the use of the enumerated lands, but rather, a discretionary authority which must be used with both wisdom and reason. The Congress does not believe, for example, that substantial numbers of people should be required to move in order to preserve these lands, or that clearly enunciated local preferences should be overruled on the basis of this authority.”

Fine, said San Antonio and Memphis planners. We already looked into alternatives that would displace more people and decided against it, so we can put that kind of consideration into writing and then move forward. Again, Congress still intended for there to be “discretionary authority” here.

Ultimately, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park sued, but no one thought they’d win. They could barely find lawyers to take the case on. But, in a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the alternative routes had not been “explored in sufficient detail.” The process was bad, so the decision was bad.

The decision cut completely against the Senate’s own report that clarified the intent of this Yarborough Rule. Thurgood Marshall and his concurring colleagues found that “green space could be disrupted, but ‘only [in] the most unusual situations.”

Ultimately, the Memphis project stalled out, because the alternative involved bulldozing many homes around the park. San Antonio built their expressway through a piece of Brackenridge Park, but only because they completely forfeited federal funds and so could skirt the rule that their own Senator had introduced.

Looking back, it’s hard to feel too enthusiastic about the specific freeways proposed here. But it’s also tough to watch the Senate pass a law with just a couple sentences in it, follow up to clarify the intent of those sentences, and then have the Supreme Court flip that intent on its head. Perhaps the Originalists had a point, but more on that below…

Ah yes, NEPA…

But Overton Park is not the only example of the Courts dramatically changing the impact of a seemingly-modest law. As many who’ve read about NIMBY issues know, the National Environmental Protection Act of 1970 (NEPA) is one of the most cited causes of gridlock and our inability to build. Most notably through its requirement for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS).

Before diving into how this all works today, let’s look into the incredibly modest original language in the bill. In the relevant section, it basically says that people should produce a detailed statement that covers:

The environmental impact

Any adverse effects that cannot be avoided

“A reasonable range of alternatives to the proposed agency action,” including the costs of inaction

The relationship between short-term uses and long-term productivity of the land

Any irreversible commitments of Federal resources

This was originally envisioned as a brief narrative, but through judicial interpretation and administrative interpretation, we ended up an incredibly convoluted process without a clear end point:

Planners and engineers began to weave the full panoply of protections into the singular process of environmental review. That then streamlined the way government weighed the impacts of any project on water quality, on noise, on historic buildings, on air quality, on endangered species, on recreation, on waterway navigability, on racial dynamics—-the list went on. A project that might impact electricity transmission lines and an endangered species and the fishing industry and a river's navigability would be brought under a single rubric, with experts from all the various responsible bureaucracies working through their separate concerns. The government would then come to a decision, mitigating those concerns to the maximum extent possible, but arriving at the public interest. But then the kicker: if the process used to reach that decision was in any way defective or deficient, outsiders were entitled now to sue on the grounds that the review had been insufficient, and courts were willing in certain circumstances to shut them down. …

Even if judges did rule in a project's favor-and in many cases, still to this day, planners and engineers do prevail— the sheer avalanche of rigmarole narrowed the scope of what once powerful bureaucracies could ever hope to accomplish. And that was the underlying point. The once powerful bureaucrat's burden under the new regime wasn't to engineer a road, or a rail line, or whatever else— it was to navigate the requirements and obstacles, to create a record of each factor contributing to a decision, and to anticipate the lawsuits that were sure to be filed against any decision. Environmental impact statements, initially imagined at NEPA's birth to be 150-page documents, eventually came to be volumes long, the length born of a bureaucratic desire to insulate any given decision from criticism that a concern had not been sufficiently considered. And that pushed many projects, both good and bad, beyond the pale of consideration.

Again, look back at the original language. It just calls for a “detailed statement.” Do you read that original language and imagine many-thousand-page documents, litigated for years? Did anyone who passed that bill think they were voting for the regime we have now?

Across these examples, a few patterns start to emerge. Some that challenge progressive instincts, and some that expose just how sticky our governing mess has become. Here are my takeaways:

Lesson 1: Beware overly-simplistic power analysis

The LEOBOR example shows this particularly well. It’s a reform that reeks of 1960s optimism and naivete, liberating men (cops) from The Man (their boss). And of course, this was also a labor rights move at the time. Similarly simplistic power analyses still prevail today, including about unions, which I think are more complicated from the perspective of Why Nothing Works and Abundance’s goal of state capacity.

Would more union power bolster the kind of powerful, New Deal-style state that many of the same progressive advocates want? Or help us have cheaper housing?

There was union resistance to California’s recent CEQA reform (their own even-worse version of NEPA), essentially because they were losing some carve-outs. Josh Barro is correct that in some Democratic jurisdictions, labor unions oppose state capacity and will need to be fought. When Alon Levy and other premier Transit Wonks examine why it costs so much more to build subways in NYC, union-mandated over-staffing is a huge contributor.

And as I wrote about while processing the 2024 election, unions don’t even seem to break Democrats’ way anymore at the national level. Politics is more and more cultural, less material. Here’s an excerpt from my previous post:

Biden did an unprecedented bailout of the Teamsters Unions’ pension fund and they still would not endorse Harris. They were officially neutral and their membership was deeply pro-Trump. Their president even addressed the RNC, despite no real track record of pro-labor policy from Republicans!

As I explore in that piece, there isn’t much electoral gain for Democrats from delivering for unions anymore, which surprises and disappoints me.

I don’t like these conclusions, they cut against my personal values and my past political history. It seems like there’s a downward spiral in the union movement, with unions prioritizing more-and-more parochial concerns as the broader movement loses power. This is a common and understandable dynamic when a resource pool is shrinking.

But that means that instead of the MTA union pushing to have more subway lines built (because that’ll mean more union jobs), they’re just focused on having redundant drivers on trains (as compared to every other country in the world). This is a short-term maximizing move for the MTA union, but I think in the long run it’s an untenable position, and frankly I hope that they lose so that the entirety of NYC can benefit from more, better subway stops and trains.

I’m not sure what the answer is, what alternative model of worker power makes sense, but I do admire the work of my friends at the Missouri Workers Center who are doing their own work to improve the labor movement.

Lesson #2: Judicial restraint has merit

Like many progressives, I have often criticized the judicial doctrine of Originalism. After all, why should views of militias from the era of the musket have such bearing on how we regulate firearms today? But I have to admit, these Butterfly Effect stories show that there’s merit to this form of judicial restraint.

Again, Originalism can seem pedantic and annoying when large value-laden cases come down to discussions of Ye Olde British Common Law. But the core idea that you should look at the intent of lawmakers and try to avoid inflating the role of the judiciary seems pretty legitimate and salient.

The case of the Yarborough Rule is particularly maddening. If Congress had intended to create a near-prohibition on disrupting green space, they probably would have just done that. Perhaps if the Court had taken less expansive interpretations there (and with the NEPA process), we’d be in a better spot today.

Lesson #3: Gridlock is real

Part of what’s depressing to me is how much this new status quo has held up. In a functioning political system, you’d expect Congress to go “oops, they interpreted the Yarborough Rule wrong, let’s pass a new law clarifying that.” Or “let’s pass a new law to clarify that we don’t intend NEPA to require reports where the appendix alone is 1,500 pages.”

But it doesn’t seem to happen, at least federally. Some of this seems to be on environmental groups, who were critical in sinking important permitting reform during the Biden Admin. In that sense, it’s a good case study of how new laws immediately create interest groups that lock them in. And it also speaks to the power analysis point above, environmental groups are not inherently good.

As I commented on Nicholas Bagley’s post about recent adjustments to NEPA, it still surprises me that there hasn’t been a more sprawling effort to repeal NEPA. I would think that Republicans would be on board, as they tend to scale back the EPA’s work whenever they get the chance. And now they could pick up some Abundance-y Democrats.

But this is also where Dunkelman’s history-without-conservatives falls short. Part of the reason that there is gridlock on these questions of state capacity is that, generally speaking, conservatives don’t care as much about the government functioning properly. In fact, dysfunctional government just gives them more ammunition to shrink the state in a more durable way.

To wrap up, these three case studies show how hard it is to write laws that age well. They show how even well-intentioned reforms can do quite a bit of damage. But, as Klein and Thompson write in the Abundance intro, this is nothing new. Every generation has its own call to reform. The challenge ahead is rebuilding a theory of governance that doesn’t rely on magical thinking about power, about courts, or about the inherent virtue of process itself.