In my last post, I introduced this series on Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland and laid out why Nixon is such a useful figure for understanding the political world we live in today. I walked through his rise—his ambition, paranoia, and skill at turning resentments into political power. He cared more than anything about foreign policy and didn’t care to challenge the liberal hegemonic hold over domestic policy. At times he would even cynically adopt liberal reforms to amass power, like in his creation of the EPA and supporting moving the voting age to 18. Finally, I brought in Perlstein’s main framework for understanding Nixon as a master manipulator of resentments who learned to exploit the cracks in the post-war liberal consensus.

In this post, I want to dig into that last facet of Nixon, one that feels resonant today. What exactly were the issues of his day and what was Nixon’s strategy to exploit them?

His political genius was in his ability to exploit the cultural divides that had opened in the late 1960s. Riots, Vietnam protests, school integration battles—all of these issues created a sense of national disorder that Nixon positioned himself as the antidote to. He mastered the language of grievance, turning cultural elites into an enemy that his coalition could rally against. He didn’t just react to the country’s divisions; he sharpened them, defined them, and made them the foundation of Republican electoral success for decades to come.

This post will dig into those core conflicts, how Nixon created the political concept of the Silent Majority, and how he rode backlash politics to a landslide victory in 1972.

The (in)famous Silent Majority

Nixon’s political thinking was embodied in a memo written by Kevin Phillips, called “Middle America and the Emerging Republican Majority.” That memo argued that:

[E]lections were won by focusing people’s resentments. The New Deal coalition rose by directing people’s resentment of economic elites, Phillips argued. But the new hated elite, as the likes of Rafferty and Reagan grasped, was cultural– the “toryhood of change,” condescending and self-serving liberals “who make their money out of plans, ideas, communication, social upheaval, happenings, excitement,” at the psychic expense of “the great, ordinary, Lawrence Welkish mass of Americans from Maine to Hawaii.”

Nixon described ‘the silent center’ as ‘the millions of people who do not demonstrate, who do not picket or protest loudly.’ They were loud. You were quiet. They proclaimed their virtue. You, simply, lived virtuously. Thus Nixon made political capital of a certain experience of humiliation: the humiliation of having to defend values that seemed to you self-evident, then finding you had no words to defend them, precisely because they seemed so self-evident.

They workshopped the concept and language from this memo a bit before finally landing on their signature concept: the Silent Majority.

What were some of the issues that divided the country and created this opportunity for Nixon to rally the Silent Majority? Principally, we’re talking about race, Vietnam, and public safety. All of these are interlinked, as the public’s sense of disorder largely (but not exclusively) flowed from protest movements for Civil Rights and against the Vietnam War.

Race and the not-just-Southern strategy

If people know only a few things about Richard Nixon, they probably know that he’s associated with the so-called Southern Strategy. Essentially, the South used to actually be a Democratic stronghold until Nixon and others in the Republican party began appealing to anti-Black racism, which helped re-align the political map towards what we see today.

This is definitely true. It was an intentional strategy, it happened. But I think it’s easy to do finger-pointing at the racist South and miss what a central role race played across the country. Nixon may have courted racist Southern votes, but he also won 49 states in 1972.

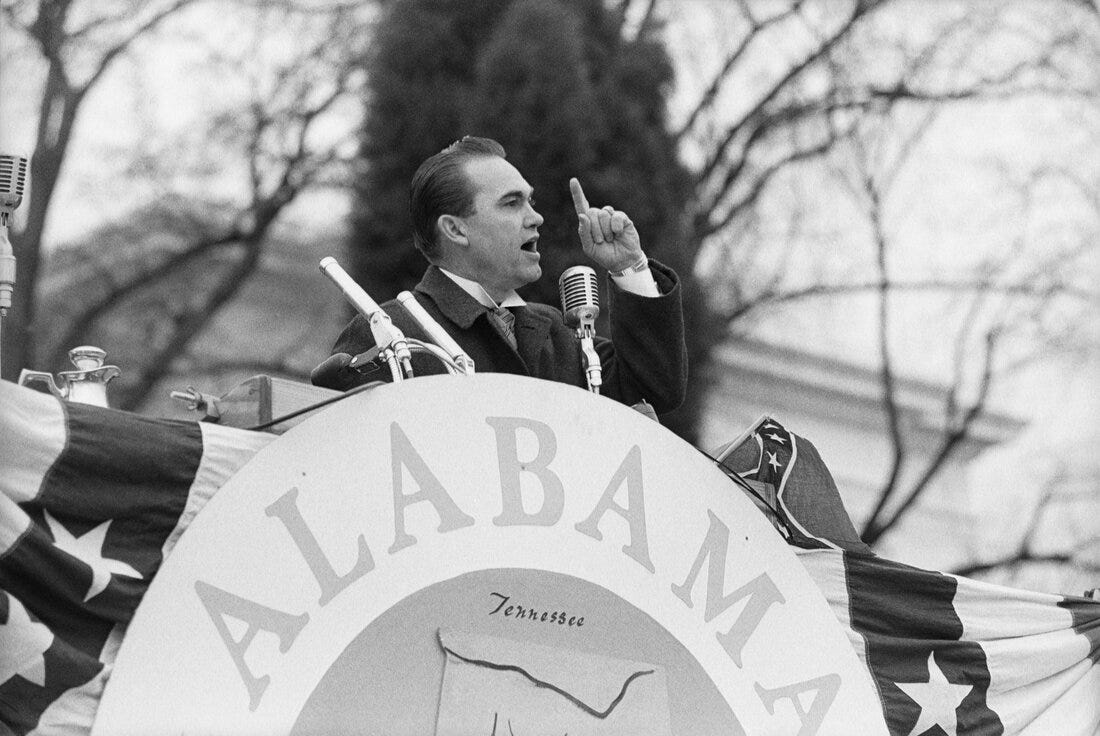

Part of the way this could be a both Southern and Northern strategy is that Nixon was great at being strategically ambiguous. It’s 1968. The Republican Party had just been disrupted by Barry Goldwater (who lost badly in 1964 against LBJ) and was debating whether to have an explicitly segregationist policy platform. George Wallace is threatening to disrupt both parties with a third party candidacy focused on segregation.

What position will Presidential hopeful Richard Nixon stake out?

He goes to a GOP event and “urged all political parties to cease using race in favor of the ‘issues of the future.’” No further comment.

Perfect! The segregationists get to say “exactly, we should stop focusing on Civil Rights!” While the polite liberal media gets to applaud Richard Nixon for encouraging his party to move on from segregation.

Much of the angst about race stemmed from race riots. These started with Watts in 1965, but continued in 1966, 1967 (most famously in Detroit), and after MLK’s assassination in 1968. These riots took place against a backdrop of Civil Rights progress and legislation on issues ranging from voting rights to housing to busing and school integration.

That last issue is one that was highly salient in the North, as people flipped out when federal funding was threatened for a very small number of non-compliant schools. It reminds me of the way that the Carter Administration threatening tax-exemption for evangelical churches made them all Republicans. Don’t mess with the money!

Urban riots and public disorder

But more often, all of the race-related issues were all sort of mashed together. Perlstein illustrates how they all co-mingled with an anecdote about Clark MacGregor, a nice Northern liberal representative from Minneapolis. School busing was leading to white backlash all over the country, but in May 1966 MacGregor had the nerve to jinx his city by saying that “racial backlash over school integration was ‘not a factor in my part of the country.’” Well good for you, many of his colleagues must have thought..

Then Minneapolis suffered a race riot. The mayor responded by proposing the creation of more jobs for black youth and white residents were furious. Why reward people who just burned our city down? By August of 1966, MacGregor completely flipped sides on the school busing debate and gave an impassioned speech against it in Congress. I want to underscore, all of this happened over three months. Social change and progress was rapid in the late 60s, but so was the backlash.

People typically identify 1968 as the big riot backlash year. As some know, political operative David Shor was fired for citing a paper on Twitter in 2020 by Omar Wasow that found that the violent riots in 1968 likely swung the election to Nixon.

The riots in this period were crazy. People picturing Ferguson riots or 2020 George Floyd riots are waaaay underestimating how violent these riots were. To pick some statistics from the Detroit Historical Society: 43 people died, hundreds were injured, there were around 1700 fires, and over 7000 arrests. If you’re more of a fiction person, Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex has a harrowing passage about Detroit 1967 (I think it’s Ch. 14).

![National Guardsmen, called in to restore order by Governor George Romney, stop their vehicle near a Detroit fire truck in the neighbourhood that was ravaged by rioting the previous day. [File: The Associated Press] National Guardsmen, called in to restore order by Governor George Romney, stop their vehicle near a Detroit fire truck in the neighbourhood that was ravaged by rioting the previous day. [File: The Associated Press]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ceQv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa94ed9ce-9b0c-48d7-acde-5001f44205f2_1000x562.jpeg)

For reference, the equivalent totals from the seminal 2014 Ferguson protests: 1 death (Michael Brown), 16 injuries (10 members of the public, 6 police officers), and 321 arrests. The entire wave of George Floyd protests around the entire nation resulted in 19 deaths and 14,000 arrests. And the 1967 Detroit riot was just one event in this 1965-1968 series of riots.

None of this is to diminish the importance of what’s happening now or to pass any judgment on the events of the past or present. But it is helpful to provide some perspective about why this period felt so disorderly and violent. It actually was more disorderly and violent than what Americans have experienced in more recent waves of social movements and protests. And it freaked people out.

But anyway, back to that 1968 electoral riot backlash. Perlstein argues that the electoral backlash actually came first in 1966, but the domestic media half missed it and half swept it under the rug:

As it had been since Tocqueville, it took foreigners to see ourselves. White House aide Ted Van Dyk reported back to Hubert Humphrey on the visit of a group of British parliamentarians: ‘They believe that backlash was far more important than it might appear to be. In district after district, and city after city, they found an undercurrent of resentment concerning civil order and gains made by the Negro population.’

Pat Brown never doubted it. His shell-shocked reaction was ‘Whether we like it or not, the people want separation of the races.’ He had a hard time processing it all: ‘Maybe they feel Lyndon Johnson has given them too much. People can only accept so much and then they regurgitate.’ Bakersfield punished its Negroes for rioting back in May by passing an initiative, by a margin of two to one, refusing federal poverty aid.

The pattern was there for those with eyes to see. The Republican won the governorship in Nebraska; in Omaha, where there had been a race riot, they picked up 62 percent more votes than four years earlier in the blue-collar wards. In Ohio, urban Poles decreased their support for Democrats by 45 percent. Thirty-six House incumbents with ratings from the AFL-CIO’s Committee on Political Education of seventy-five or higher were defeated—especially traumatic since Republicans had filibustered labor’s fondest legislative wish: a repeal of the right-to-work provision of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act. Union members voted for politicians who weakened their unions because the Democrats supported civil rights. Some confused backlashers even voted for Edward Brooke because he had an (R) by his name. Though voters who knew he was black told reporters things like “It’s nothing personal, but if he got in, there would be no holding them down; we’d have a Negro president.”

The Kerner Commission

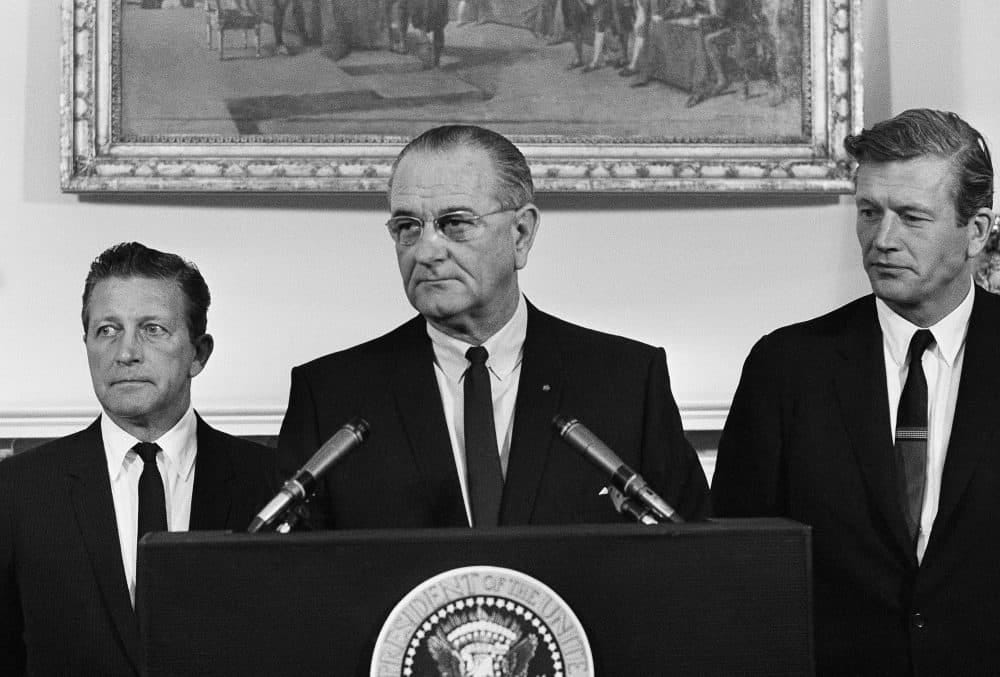

That’s 1966. By 1967, the riots hadn't stopped and LBJ established the Kerner Commission to get to the bottom of it. They released their report in February 1968. LBJ knows that the politics here are tough and the Civil Rights advancements he’s helped get through are in jeopardy, so he wants a pragmatic and cautious report ahead of the 1968 Presidential election.

John Lindsay, Mayor of New York and Vice Chairman of the Commission, had other plans. Near the last minute, he sneaks in MLK’s goal of $30B in new urban spending as a recommendation. But more importantly, he added a famous introduction that directly assailed America’s racial inequality and blamed white Americans for the condition of Black Americans, the real cause of the riots.

Remember how this turned out in Minneapolis? White people don’t like being blamed and called racist. Literally a day later backlash to that Kerner Commission report (particularly the firebrand introduction) almost sunk a new Civil Rights bill in the Senate. It barely squeaked by, in part because an amendment was attached “that made it a federal crime to travel from one state to another with the intent to start a riot–rammed through even though Vice President Humphrey, presiding in the Senate chamber, ruled the amendment procedurally out of order.”

LBJ was a savvy enough politician that he knew that these were cursed politics:

The President was aghast at the Kerner Commission report. It did the one thing he’d been so careful never to do when laying the political groundwork for his sweeping social and civil rights legislation: blame the majority, instead of appealing to their better angels. None wanted to be hectored as oppressors. They thought they had enough problems of their own.

Vietnam looms large

Whew. So that’s the race issue. Charged stuff. Good thing there wasn’t anything else big and controversial going on.. Oh wait, Vietnam.

There was a tremendous amount of press complicity and essentially elite collusion to hide the worst of the Vietnam War from the public for a long time. I talked about this a bit elsewhere in my post on Martin Gurri and populist sentiment. When the truth started to leak out due to press leaks, veteran testimony, and more, people were beyond outraged.

It’s hard to overstate the impact of that fallout and the anti-war movement on US politics and Nixon’s rise to power. It divided the Democrats, undermining the Great Society coalition. This ultimately forced LBJ to not seek re-election, but do so pretty late in the game in 1968 in a way that led to chaos within the Democratic Party.

Like with race, Nixon carved out a lot of strategic ambiguity in Vietnam. He’s all about “ending the war,” but at times this is read as more hawkish, at times as more dovish.

What did he actually believe about Vietnam? Nixon once confided to a colleague:

“Nixon,” said [Elmer] Bobst, “agreed that Vietnam could not be ‘won’ and that we would eventually have to withdraw.” That withdrawal, however, must take place under the most strategically propitious circumstances–whether they be one, five, or ten years in the future. Until that time, the public would just have to be told what the public had to be told.

A morally enormous position, perhaps. But a rather politically advantageous one. Nixon had given himself license to lie about Vietnam. The trick was devising the most politically useful lies for any given interval. Hindsight makes the pattern obvious. Nixon had taken just about every possible position on Vietnam short of withdrawal—we should escalate, we should negotiate, we should bomb more, we should pause the bombing, we should pour in troops, pouring in troops would be a scandal. Liberals who paid attention were enraged. They congratulated themselves for spotting the hustle. It hardly bothered Nixon; their derision only helped him with the Orthogonians. He was receiving little coverage during those eventful months. It took someone with the eye of a hawk and the obsession of a neurotic to mark all the twists and turns.”

In practice, he embraced a strategic form of hawkish, erratic behavior and intimidation:

“I call it the madman theory, Bob,” the Republican presidential nominee had told his closest aide, walking on the beach one day in 1968. “I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that ‘For God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry—and he has his hand on the nuclear button.’ And Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.”

Remind you of anyone in contemporary American politics? Anyway, this.. did not end up actually working in Vietnam after Nixon was elected. But he really played the electoral politics well.

Similar to how the media and establishment misread the signals about the 1966 midterm backlash about race, Nixon picked up on the ambiguous signals from the public about Vietnam that others missed. Eugene McCarthy did well in early primaries against LBJ in 1968, which was read as anti-war, anti-LBJ sentiment. But the story is more complicated:

Later, two polling experts, Richard Scammon and Benjamin Wattenberg, looked more closely at the data and learned that 60 percent of the McCarthy vote came from people who thought LBJ wasn’t escalating the Vietnam War fast enough. They weren’t voting for McCarthy because he was “liberal.” They pulled their lever for him, Scammon and Wattenberg convincingly argued in a book, The Real Majority, that came out two years later, because they were “Fed-up-niks.” They saw McCarthy as an alternative to the status quo, and the status quo was a nation gone berzerk.

Nixon ultimately gave voice to that anti-status quo, populist sentiment in a way that caught the liberal media off guard. Remember that we’re talking about populism and this is a great example of how hard it is to read anti-establishment sentiment. Think in the modern day of Obama-Bernie-Trump voters.

Finally, it must be said that Nixon also crossed a pretty insane line in his quest for power. He actively worked to undermine the Paris Peace Talks between the North and South Vietnamese to keep the war going:

But Nixon couldn’t be elected to produce peace if peace had already been produced. And in Paris, the chances of peace seemed to be receding every day. Every time the North Vietnamese appeared ready to agree to a condition, the South Vietnamese raised the bar.

The reason was that Nixon had sabotaged the negotiations. His agent was Anna Chennault, known to one and all as the Dragon Lady. She told the South Vietnamese not to agree to anything, because waiting to end the war would deliver her friend Richard Nixon the election, and he would give them a better deal.

I’ve mostly avoided editorializing and tried to just present the history, but suffice to say that this is unbefitting conduct for a public servant and it’s this kind of insane, unchecked ambition and all-consuming quest for power that led Nixon to be impeached and resign.

The Anti-War Movement and even more backlash

I imbibed a somewhat rosy, left-leaning view of the 1960s from pop culture and a liberal environment in Seattle. Over time, that view has been punctured. I remember picking up Joan Didion’s “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” in college and thinking “wait, there were reasons that the hippies were bad? They weren’t just the lovable goofs of peace-sign-Halloween-costumes?” (Side note, it’s interesting how much liberals love Joan Didion given how conservative she is, but I guess that’s the power of amazing writing.)

To pick another example, I thought the public was broadly on the side of the Chicago DNC protests and the Kent State students and that campus protests like Kent State were nonviolent. It turns out that at Kent State (and other campuses, including my alma mater) there was attempted and successful arson targeted at ROTC buildings, throwing rocks at police, etc. Much more disorderly than I had thought, not just hippies flashing peace signs.

Let’s look at Kent State. There had been plenty of unrest, including some violent acts on previous days, and eventually the National Guardsmen murder students in cold blood. Not even editorializing here, they’re under no immediate threat and basically just drop to their knee and shoot a bunch of students who are far away, two of whom are not even part of the protest. It’s terrible, I grew up with Neil Young’s “Ohio,” a composition of howling grief about the incident, and just sort of assumed that Young’s response reflected the period.

For context, it was initially thought that two guardsmen died, but that was quickly cleared up in the press. Here’s some of the reaction that followed:

When it was established that none of the four victims were guardsmen, citizens greeted each other by flashing four fingers in the air (“The score is four / And next time more”). The Kent paper printed pages of letters for weeks, a community purgation: “Hurray! I shout for God and Country, recourse to justice under law, fifes, drums, marshal music, parades, ice cream cones—America—support it or leave it.” “Why do they allow these so-called educated punks, who apparently know only how to spell four-lettered words, to run loose on our campuses tearing down and destroying that which good men spent years building up?… Signed by one who was taught that ‘to educate a man in mind and not in morals is to educate a menace to society.’” “I extend appreciation and wholehearted support of the Guard of every state for their fine efforts in protecting citizens like me and our property.” “When is the long-suffering silent majority going to rise up?”

It was the advance guard of a national mood. A Gallup poll found 58 percent blamed the Kent students for their own deaths. Only 11 percent blamed the National Guard.

This kind of widespread public hatred of protestors was pretty common. The violent crackdown on protestors at the DNC in Chicago was so egregious that even a pro-cop columnist condemns police actions.. Only to find out that “the great majority of Americans sided with [Chicago Mayor Richard] Daley” and the police.

When you read some of the descriptions of famous university protestors it’s evident why many Americans have a distaste for them. Here’s a profane anecdote about the Columbia protest, instructions given from a protest leader about how to interact with the police:

“So here’s what we want to do…. Pick up your shirt. They won’t know whether to jerk off or go blind…. Tell ’em their mother sucks black cocks or takes black cocks in the ass. The important thing is you got to use these words. I know that can be tough. We aren’t all completely liberated. But if we use words like suck about their mother, these fucking cops will blow like a balloon.”

Working-class cops had to stand there and watch as a young girl walked down the line of mediating professors shouting, “Shit! Shit! Shit! Shit!” and cried, “Go home and die, you old people, go home and die”—and think, how nice to be able to have professors. Seven busloads of tactical police sat fondling batons. They assumed the kids were stockpiling Molotov cocktails—they called themselves revolutionaries, didn’t they? “If we had held them in that bus much longer, they would have hit us,” a mayoral aide recollected. Finally the police got the signal—and stained ivy walls in a bloody mass arrest.

The last act at Columbia took place on May Day. A small number of policemen remained behind on campus to maintain order. One bent down to pick up his hat after a kid knocked it from his head. At that moment, someone leapt on his back from a second-floor window. The cop spent the next twelve weeks in the hospital.

The cops got the confrontation they wanted. The revolutionaries got the confrontation they wanted. Lo, a new crop of revolutionaries; lo, a new crop of vigilantes: Nixonland.

Perlstein is also good at documenting that there was indeed right wing vigilante violence. But this was not perceived by the public as a symmetrically violent time, the blame fell on the Left. The press tended to cover the left wing violence, but not the right wing violence, and Perlstein provides plenty of examples.

As is suggested by the Kent State, Chicago DNC, and Columbia anecdotes above, the public was often against the idealistic leftie revolutionaries. And when we marry that with the anti-black backlash from race-related riots, you end up with quite a law and order moment. The Warren Court’s expansion of rights for defendants and suspects (think Miranda rights, which came about in 1966) helped fuel this backlash.

Essentially the right-wing sentiment at the time was: “our streets are burning, the universities are full of students spitting in the face of cops and throwing rocks at them, why in the world is the Supreme Court so concerned with giving cops, prosecutors, and judges less ability to act?” Here’s Nixon, as always, giving his own sharp point to the issue:

Nixon wrote a big article for Reader’s Digest called “What Has Happened to America?” that bemoaned riots, racial animosity, and more. He blamed it on the elites: “Our opinion-makers have gone too far in promoting the doctrine that when a law is broken, society, not the criminal, is to blame.” “Our teachers, preachers, and politicians have gone too far in advocating the idea that each individual should determine what laws are good and what laws are bad, and that he then should obey the law he likes and disobey the law he dislikes.” “Then Nixon introduced a refrain for his 1968 stump speeches: the ‘primary civil right’ was ‘to be protected from domestic violence.’

Love him or hate him, the man knew how to coin a phrase.

In my next post, I’ll take a step back from Nixonland to look at how it actually felt to live through this period. My main text there is Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, a masterful exploration of the generational divides of the time. And finally, I’ll close out the series with reflections on what all of this means for today and whether we ever really left Nixonland.

Thank you for putting the Nixon presidency in its social context.

You make a glancing allusion to the influential work of Scammon and Wattenberg on the American electorate. They are now associated with the pithy formula (which is not really theirs but is an apt summary) of the typical voter being “non-black, non-poor, non-young”. This remains largely true today and goes far into explaining the lack of sympathy - even the antipathy - towards rioting mobs, including of students. Further, just as today, lefty opinion-makers dominated the media and gave substantial air cover to the disorder, while mercilessly attacking Nixon for his anti-communist record, and therefore giving affront to the values of large swaths of the population.

In short, it is no surprise that broad resentment built up in the electorate against domestic violence and their supporters. Nixon did not invent it, but skillfully capitalized on it, as you indicated. The important thing is that, just like in today's MAGA moment, there was a large constituency that felt alienated and taken advantage of. Perhaps in contrast with today's MAGA standard-bearer, Nixon was also probably sincere in his oft-expressed dislike of "coastal elites" (I think the expression dates from that time): smooth and Ivy-educated, connected and moneyed, Kennedy-type establishment, etc., as he grew up in modest circumstances in the then-peripheral state of California, was socially awkward and always carried a chip on his shoulder about it.

And yet, he was a remarkably popular president until he was felled by the Watergate incident, something that has been obliterated by later (again, lefty and vengeful) opinion-makers.