Why Nothing Works and The Do-Gooders Who Can’t Do Good

Voice, Veto, and the $1.7M Toilet

Mark Dunkelman’s Why Nothing Works is such a strong companion to Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance that you’d think they all coordinated it. To reiterate, the general Abundance argument was:

We need to build and invent more in a number of crucial areas (e.g., housing, healthcare, public transportation, green energy),

Both Democrats and Republicans have hamstrung the government so that its ability to execute in these areas is low (aka there is low “state capacity” right now),

These problems are worst in places like California where liberals govern,

Democrats and liberals need to stop hobbling the government and help increase state capacity so that the state can play a crucial role in building out the supply of some of the areas listed above.

More of my favorite parts, takeaways, and lingering questions from the book are here in my review from April:

Abundance is a high level gloss, a political manifesto. It has some historical background, but it primarily describes the problems of the present and sketches a broader political agenda, focused on supply and deregulation with progressive ends.

Dunkelman makes a very similar argument, though he’s much more academic. Both in the sense that his book is more jargon-y (see below) and that it gets a bit more into the weeds: lots of history, lots of case studies, and a clear discussion of policy tradeoffs.

All of this helps flesh out the story of why exactly we ended up with such a sclerotic government. Understanding that history can hopefully help Abundance advocates avoid the mistakes of their forebearers.

In this post, I’ll lay out the core ideas of the book and reflect on why it matters right now, including::

How progressivism got pulled apart by two competing visions of power,

The deep historical roots of this disagreement,

Why Dunkelman thinks things went off the rails, with case studies to prove it,

His proposed path forward (“voice but not veto”),

Some hard questions that still linger

Battle of the Founding Fathers

Academic books often do a great job of concisely stating their theses, so here’s him breaking down his “three arguments” in his introduction (emphasis added here and elsewhere):

The first, to recount, is that progressivism is defined not by one, but rather by two divergent impulses. The second is that the two impulses have waxed and waned through time such that the movement's underlying zeitgeist has shifted, a bit like the tide. And the third, made so plainly evident by the catastrophe at Wollman Rink, is that the balance that's emerged since the late 1960s—the excessive tilt toward the Jeffersonian—is a seminal political liability for the progressive movement.

What are these two impulses? He calls them the Hamiltonian and the Jeffersonian, named after two Founding Fathers who famously argued over the role of the federal government.

Hamiltonianism is a preference for a strong, centralized government, Jeffersonianism for a more decentralized society focused on individual rights. Sometimes people associate the former with liberals or Democrats and the latter with conservatives or Republicans, but Dunkelman argues that you can tell a complete story of these warring impulses that’s completely contained within progressive politics. For example, let’s take some of the achievements of LBJ and the Great Society:

The Voting Rights Act was not more progressive than the creation of Medicaid, or vice versa. Nor would creating a Marshall Plan for Black communities have been more progressive than passing the Civil Rights Act. But these various ideas were distinct from one another in that they were steeped in different conceptions of power. Those who believed centralized power was a force for good were more likely to want to empower bureaucracy. Those who thought it inherently bad were more likely to want to burnish individual rights.

Again, we’re talking about a deep cleavage in American politics about power that inspires disagreement in both parties and often varies issue-by-issue. A conservative like George W. Bush was a Jeffersonian about religious minority rights while also being a Hamiltonian who consolidated extensive power in the Executive Branch post-9/11.

Dunkelman’s need to constantly reference Hamiltonianism and Jeffersonianism is a little obtuse and jargon-y, but it does foreground how deep the roots of this intra-progressive conflict are.

Progressivism imbalanced

I also appreciate that he isn’t arguing for one of these two approaches in any dogmatic or fundamental way. He rightfully believes that there will always be this push and pull, as there has been for the roughly 250 years of America’s existence. His point is just that things have gotten out of balance:

By tipping the scales too far from Hamiltonianism, and too far toward Jeffersonianism, progressivism became, in short, a movement of do-gooders unable to do enough good.

Side note, the book is full of punchy sentences that sum up progressivism’s current issues. I highlighted many, but just quote this one. Anyway, keep going Mark:

But the most profound detriment of the system Jeffersonian progressivism has created is that it has made government, in many realms, authentically incompetent. That, as we'll see, has now become progressivism's great political burden. Who in their right mind would seek to give more power to this sort of dysfunctional, do-the-least-possible version of government?

Ouch.. But perhaps an appropriate description of cities like San Francisco that require $1.7M to build a toilet in a park.

In the standard left wing telling, this kind of dysfunction (or “reduction in state capacity”) is a result of neoliberalism and figures like Ronald Reagan, who disinvested in the public sector. But Dunkelman is very clear-eyed that progressives deserve some of the blame for hobbling the state. After all, conservatives are not behind the $1.7M toilet in San Francisco.

I think plenty of people on the left will find Dunkelman’s story frustrating. After laying out his argument, he essentially offers what I’d call an overview of American political history since the Gilded Age where conservatives don’t exist. It’s not that figures like Ronald Reagan don’t appear at all, but Dunkelman is trying to prove his point that you can tell a relatively complete story of how our politics became so imbalanced without blaming conservatives.

It’s a useful thought exercise. For one, it’s better than just shaking your fist at neoliberals, as many lefties do today. Essentially, saying those who hobbled the state were fake progressives. But they were progressive, and ignoring that fact makes it harder to solve the problems they created.

As Dunkelman says, “there's nothing wrong with progressivism that can't be fixed by what's right with progressivism. But to restore the movement's promise, we will need to grapple with our own demons, and place our good intentions in a balanced, productive tension.”

The OP’s (Original Progressives)

So how did we get here? Before diving into modern case studies, Dunkelman starts with the original Progressives and the political fights that shaped their thinking. The history here is impressive in both its depth and its breadth.

In the Gilded Age, an era of unprecedented wealth accumulation, the impacts of rising corporate power and monopoly were hard to ignore. Louis Brandeis is one of the most famous Supreme Court Justices of all time and a cornerstone of the antitrust movement. He, Teddy Roosevelt, and Populists like William Jennings Bryan all wanted to confront these big trusts, but had different visions of how to get there and what society should look like instead.

Brandeis and Bryan envisioned a society with smaller businesses, but also smaller government. Their preference for smaller-everything is still an animating force in the (fittingly) small-but-loud leftist antitrust movement today, as Matt Yglesias argued in a recent post:

Teddy Roosevelt, on the other hand, wanted to build up a federal government with a professionalized administrative state. This effective, centralized state government could adequately counterbalance the power of big business.

In a phrase that may have inspired Dunkelman’s book framework, “New Republic founder Herbert Croly had, in 1909, defined the progressive creed [i.e. Teddy Roosevelt’s approach] as employing "Hamiltonian means" to achieve "Jeffersonian ends."”

With that foundation in place, Dunkelman moves into the meat of the book: how these competing visions played out in actual government programs.

Case Studies Galore

The book moves through case studies of different policy domains like housing, highway construction, and energy permitting. Over and over again, Jeffersonianism wins out over Hamiltonianism and the government gets less effective.

Most of the chapters open with some sort of extended case study, which are generally fantastic. I learned a lot about the Tennessee Valley Authority, for example:

The TVA, still in operation as late as 2025, would come to construct sixteen dams - a feat of engineering, many have argued, equal to a century's worth of the nation's railroad construction combined. And that publicly constructed system not only electrified vast swaths of the countryside-millions of dusty acres were turned into arable land, two hundred million trees were planted, erosion was curtailed, and farms and businesses both began to thrive. Despite displacing as many as fifty thousand people, the TVA was so successful that even conservatives lauded it. Representative John Rankin, an unrepentant racist from Mississippi who would become Senator Joseph McCarthy's red-baiting ally, argued years on that "TVA is the most profitable investment the American people have made since the Louisiana Purchase.”

But, to illustrate Dunkelman’s point: can you imagine a project today coming from the Left that displaced 50,000 people? That would never happen in a million years. But this was seen as the price of progress. And it produced unexpected benefits. During Eisenhower’s Presidency, one of the TVA dams created a “little peninsula of unused land” that an employee saw and almost instantly turned into Land Between the Lakes in Kentucky and Tennessee. More than a million people go there every year.

Again, could you imagine any of this happening today? Maybe on a 30-year timeline, but even then I think it’s unlikely.

When the federal government funded protestors

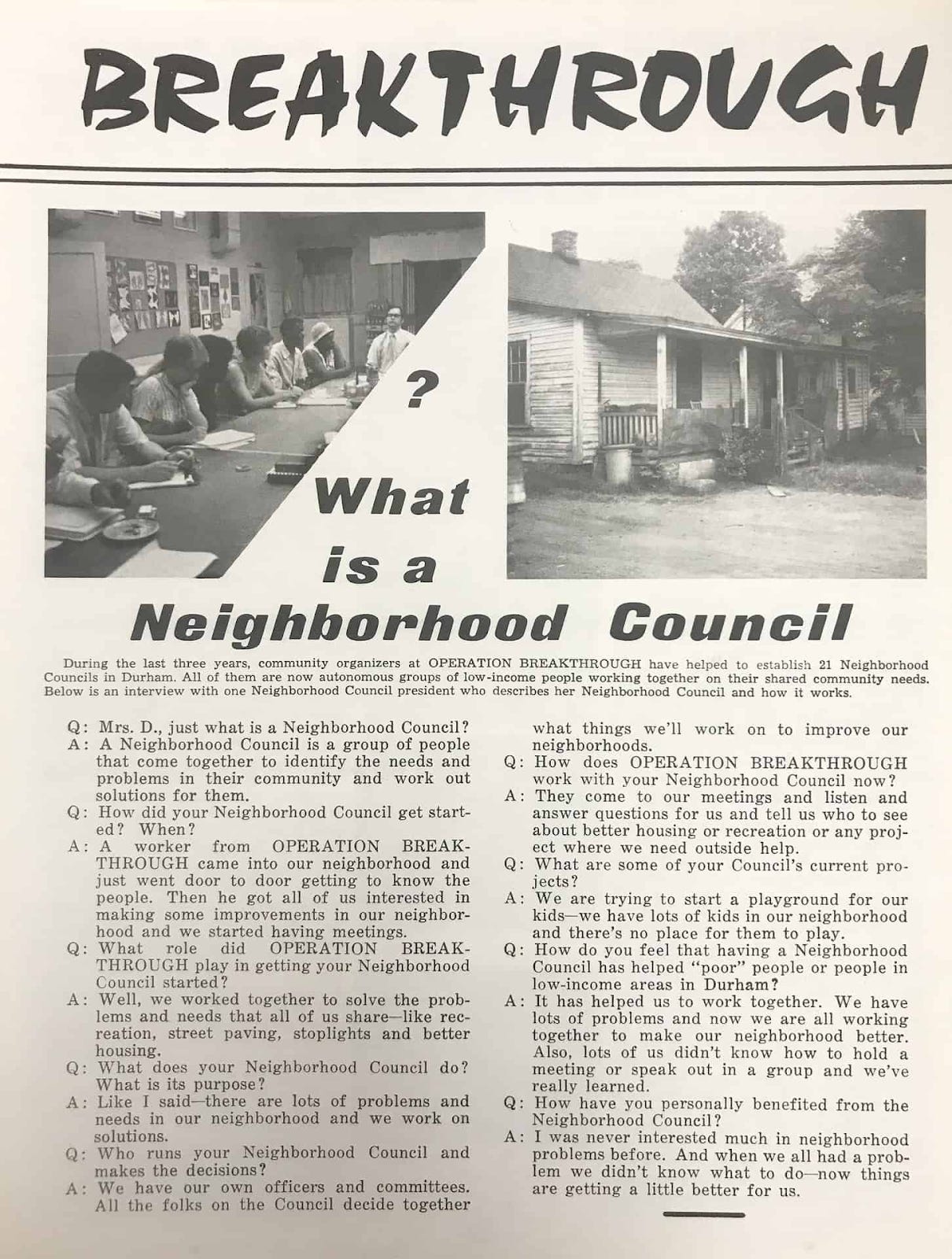

Another case study about Community Action Agencies stuck out to me, because it came up in my recent writing on philanthropy as an example of a program scaled by the federal government after being piloted by the Ford Foundation. CAAs sort of feel like the far edge case for the Jeffersonian impulse, and it quickly blew up and led to a retreat by the Johnson administration.

LBJ’s Office of Economic Opportunity created the Community Action Program (CAP), to bring about the “maximum feasible participation” of the poor in government welfare programs. Money was channeled to Community Action Agencies (CAAs), many of which still exist today.

Dunkelman traces the story of how CAA funding bloomed from hundreds to thousands of agencies and was putting money directly into the pockets of community organizers “explicitly promising to agitate against housing authorities, welfare agencies, and perhaps most of all, elected politicians who were, in many cases, the president’s most ardent supporters.”

Within a couple of years, the pushback from local elected officials was too strong, and LBJ signed a bill “redirecting the program's funding to local governments; rather than fuel those agitating against the Establishment, CAPs would fund... the Establishment. … And with that, a program designed to be a cornerstone of Johnson's war on poverty was shunted to the margins, a well-intentioned initiative that appeared, from both liberal and radical perspectives alike, to have gone haywire.”

It’s interesting, because on the one hand this is an example of philanthropy successfully piloting a model of services and then getting the federal government to take it on. But in this case the most radical part of the program (funding community activists and involving them in the design and implementation of government programs) was rolled back very quickly because the government is subject to political pressures that philanthropy is not. It was never going to be sustainable for the federal government to be directly funding anti-government agitators, regardless of the merits of their cause.

Community Action Agencies still exist today and administer a lot of important programs, but it’s not surprising that funding community activists was a Jeffersonian bridge too far.

But this is a rare case where Jeffersonian progressive policy was immediately rolled back. As Dunkelman shows, the broader theme is that the government loses power and the ability to do anything. Eventually, as the title says, Nothing Works. It’s pretty bleak! But Dunkelman does offer a path forward.

Voice, but not veto

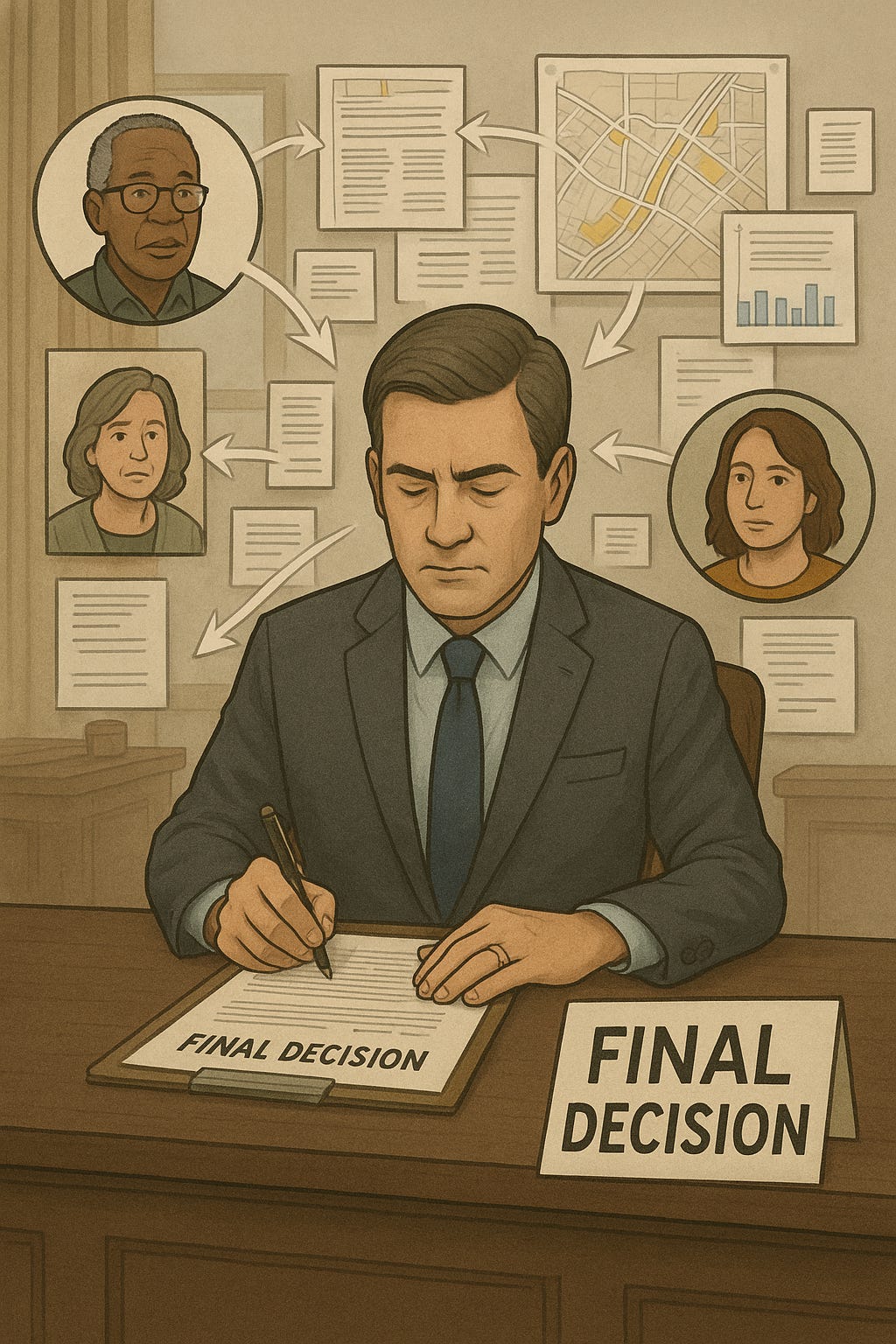

Dunkelman’s suggestion is this: we need a government process that provides people with a voice, but not a veto.

Basically, we ended up in this situation because the government did bad things, trampling on people’s rights and not listening to those they negatively impacted. Infamously, Urban Renewal planners bulldozed many minority communities to clear “slums” and build freeways. Bob Moses is the famous example, largely due to Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, but there are rhyming dynamics in most of the policy domains that Dunkelman covers.

We ended up in this overly-Jeffersonian kludgeocracy because people fought to have a voice in these kinds of decisions. Which was a good correction! We’ve just taken it too far.

At this point, the government is stuck in the middle of a bunch of voices and faces the threat of a lawsuit over all sorts of elements of the process, whether it be energy transmission buildout or highway construction or permitting housing. The process is amorphous because you can delay and stall, effectively exercising a veto because the more the process lengthens, the more expensive in time and money it is.

But we can’t just pendulum swing all the way back to Bob Moses. For one, the government does a lot of bad stuff when it does not adequately take minority interests into account. Even if we wanted to go back to that era, it just wouldn’t be politically sustainable and would be quickly reversed.

The solution, Dunkelman argues, is a middle path: weigh community voice more highly than Bob Moses did, but give the government the power to render an ultimate decision that is not endlessly litigated and appealed. If people don’t like the outcomes, that’s what representative democracy is for. So add a third “v” to the list: vote.

Here’s hoping that we are able to arrive at this kind of middle path, but I have some worries.

Hard Questions for the Abundance Agenda

Here are some of my unresolved questions, not about Dunkelman’s diagnosis, but about the path forward. I had some of these questions when I first read Abundance, but Dunkelman’s book helped sharpen my thinking here.

1. Do Americans actually like status quo stasis?

I worry that status quo bias is too high these days, particularly given the high material standard of living of your average American. In a lot of ways, this is good. My fear of a second American Civil War is pretty low because who really is going to go shiver in a trench and get gangrene in 2025? People’s level of comfort is just too high. Easy to mouth off on a gun forum, but then they go back to watching TV like everyone else.

But the flip side is that people just don’t like change. G. Elliott Morris had an article in Catlist a few years ago showing a consistent, non-partisan status quo bias in ballot initiatives. This also is represented via what is called thermostatic public opinion. When Donald Trump is President and tries to get rid of immigrants, people go “wait, I kind of like immigrants!” And then when Biden is President and immigration ticks up, they go “we need less immigration!”

The upshot of this is it leaves me wondering: do we have a government that doesn’t work because people don’t want a government that works? And if they don’t want it to work, how long can we run back the Progressive Era or New Deal playbook before we just creep back to the kludgeocracy. People grumble about the current inability of the government to accomplish anything, but in practice they may get more worked up by big changes that impact them.

As I said, I wonder if this is downstream of the relative material abundance and high standard of living that your average American has now. One of Abundance’s motivations for strong state action is the need to confront climate change. But do people really want the government ruffling their feathers and disrupting their lives to build high-speed rail to solve a more amorphous problem like climate change with costs in the future that will largely be borne overseas? That’s much less immediate than the benefits that everyone received from the TVA, including electrifying their homes.

2. How do you tell when people genuinely have “voice” in a process?

I also wonder how well citizens can differentiate between voice and no voice. There’s already so much essentially-fake community engagement that the government does, where they already know what they’re going to do, so they just check the box. This kind of empty voice really pisses people off, understandably so. And even if you are listened to, people probably won’t feel listened to if the final decision goes against their wishes.

My godfather lived on Whidbey Island in Washington State. The military had a base nearby and they moved some very fast and very loud aircrafts there. They flew multiple times a day and were so loud that they rattled everything in the cabinets and made it impossible to carry on a conversation. You can hear how loud it is in this University of Washington video:

And you know what? They did all the annoying process stuff. They did a big Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), they met with community members, they did the whole “voice” charade. But they were always going to fly those jets. My godfather ended up selling the house and getting out before the plane traffic got to full volume, but lost a ton of value on the home.

So the government can still take action like this that adversely impacts smaller communities. It’s just mired in a ton of fake process that doesn’t actually give anyone any voice. They weren’t seriously weighing environmentally-sound alternatives in their EIS.

Basically everyone loses here: taxpayers foot the bill of millions and millions of dollars spent on hearings and the EIS. Local residents lose quality of life and home value. And you add insult to injury with a fake engagement process.

In this case, I’d rather just be honest that those people don’t actually have a voice. But I also think that if you move more towards “voice, but not veto,” you’ll still get a bunch of people complaining about not having a voice because it’s quite hard to tell the difference.

3. Will corruption sink the ship?

Finally, I’ll end on a point that I made in my Abundance review. I think the biggest Achilles Heel here is the prospect of political corruption. Many of the messy processes we have were a response to criminal and unfair governance. Many steps in the process are to add transparency and accountability to stop graft or other corrupt practices. Removing those steps will almost inevitably lead to a higher rate of corruption.

It’s probably a tradeoff worth making. If we streamline the construction process and save $600M in the construction of a new high speed rail line, but $1M ends up siphoned off via corruption because we simplified the process and reduced transparency, is that so terrible? But that’s a really terrible way to sell this transition. The politics are so bad that I hesitate to even write that down.

The hope is that people would love the outcomes. They’d see corruption as “the price of progress,” much like people describe the 50,000 people displaced for the TVA. But I just really doubt that’s how our politics would work today.

For one, like I said in point #1 above, most people have much less to gain from drastic government action than they did in the TVA era. But more generally, the idea that the public will reward politicians for accomplishing things, often called “deliverism,” is pretty flawed. Voters seem to punish politicians for even great accomplishments. I wrote about Bill de Blasio’s stunning Universal Pre-K success, and yet everyone hated him at the time. On the other hand, there is a surprising resiliency to corrupt politicians, including our President. So maybe corruption wouldn’t sink the ship the way I think it would.

So while I ultimately love Abundance and Why Nothing Works, it will be a difficult reform agenda to pull off. But Dunkelman’s work is an incredibly important piece of the puzzle and if these were easy problems to solve we would have solved them by now. He digs deep into the past, helps explore how the government got so tangled up, and is clear-eyed about tradeoffs and tensions that will never vanish from American politics. If we’re serious about building again, this is the kind of political honesty we need.

Great review. I'm going to have to read this book. I really thought I had finally beaten academic consensus (https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/04/17/learning-to-love-scientific-consensus/) with my neoprogressivism take, but I should have known. I really like your hard questions! They're clear and do get at knotty issues with the Abundance agenda. Some thoughts.

For 1, I wonder how much of this is based on age demographics. With the Baby Boom generation, American age demographics have gotten more and more top-heavy, with seniors and older people being a larger proportion of the country. I think there are strong reasons to believe that older people have less upside for getting new things and more downside for losing old things, and also may be more risk-averse and nostalgic (can expand on this if it's not clear). Will these change as Boomers die? I don't know the stats on this.

It has been reported that the youth (Gen Alpha and such) report feeling that community engagement is less important and making money is more important. This has generally been reported as a bad thing (understandably), but isn't another way of looking at this Gen Alpha wanting to take the Hamiltonian bargain instead of the Jeffersonian? Hamiltonians say "we'll make you rich, but let a centralized decision-maker do the policy while you run around making money" while Jeffersonians say "you'll all have rights and take part in decisions."

For 2, I think this is really important, but not necessarily fatal. There are consistent studies showing that people feel better after having their case heard in court even if they didn't win, so voice is not nothing---people can feel better about being heard (this academic review of the literature is just the first thing that popped up when I searched for something like this: https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.1.041604.115958). Now, courtrooms have a lot of history and cultural symbolism backing them up on this matter---"having your day in court" is an idiom for a reason. I'm not sure how well other agencies can do it, but there are definitely ways for it to work. The main problem with voice and veto is probably a vocal minority, silent majority issue. I am really skeptical about this part, though, and my thinking is sometimes that maybe the lesson from Robert Moses is just to make better decisions? Like maybe it's just we need to substantively make better decisions and trying to solve it by process is wrong. Matt Yglesias also has a good post about how many of Robert Moses's general principles were just bad from a modern economic point of view: https://www.slowboring.com/p/robert-mosess-ideas-were-weird-and.

For 3, I think Dan Davies is talking really interesting stuff in Back of Mind and in his book The Unaccountability Machine on management cybernetics and organizational decisionmaking. He's had some recent posts about how information processes in government action and how they turn into corruption. I also am reminded of Matt Levine, who writes Money Stuff, where I think one of his lines is something like "the efficient level of fraud is not 0."

You make a good case that it’s completely implausible that progressives will get around to building things. Indeed, they can’t stomach being mean and asserting the interest of the majority (in your post, you showed a strong pro-minority bias, if you noticed). Thus, they can’t “sacrifice” anybody- and therefore, nothing will be built by progressives. The whole “abundance” fad is a good diagnosis, but is DOA as a program.

By other political groups, perhaps: for instance, one that would emphasize “greatness” and was willing to show a mean streak.