Process Is Not Progress: My Abundance Review

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson's new book reminds us how far we are from effective government

My first impression of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new agenda-setting book Abundance is that it’s obviously correct. It’s a wonderful synthesis of the best of right-wing and left-wing thought with the goal of increasing the state’s capacity to achieve liberal goals. They take to task the failures of American governance, particularly in Blue states like California, and their inability to build and innovate. They’re liberals and the book is explicitly framed as a self-critique.

In some sense, that could be the whole book review. Klein and Thompson have been on the right track on these issue for years. This book concisely and clearly pulls together all the threads that they’ve been exploring in their writing and podcasts over the last few years. It’s a quick read, it’s accessible, I hope every Democrat (and Republican) reads this book and adopts it.

The book is worth exploring in more depth. Especially because its core ideas are persuasive run headlong into the messy realities of politics, bureaucracy, and trust. So I’ll start with an overview, dig into a few parts of the book that I thought were sharp (particularly their case for implementation science). Finally, I’ll touch on an area of potential backlash that the book underplays that could sink the whole Abundance project.

Overview: a new framing for American politics

The introduction is a sort of sci-fi vision of abundance, a sort of Star Trek-style bountiful future. But the conclusion is where they best lay out their ideas in the model of a typical introduction:

Abundance reorients politics around a fresh provocation: Can we solve our problems with supply? Many valuable questions bloom from this deceptively simple prompt. If there are not enough homes, can we make more? If not, why not? If there is not enough clean energy, can we make more? If not, why not? If the government is repeatedly failing to complete major projects on time and on budget, then what is going wrong and how do we fix it? If the rate of scientific progress is slowing, how can we help scientists do their best work? If we need new technologies to solve our important problems, how do we pull these inventions from the future and distribute them in the present?

They reframe the typical divisions in American politics:

We are used to understanding the battle lines of American politics as cleaving liberals who believe in a strong, active government from conservatives who doubt it. The truth is far more complicated. Liberals speak as if they believe in government and then pass policy after policy hamstringing what it can actually do. Conservatives talk as if they want a small state but support a national security and surveillance apparatus of terrifying scope and power. Both sides are attached to a rhetoric of government that is routinely betrayed by their actions. The big government-small government divide is often more a matter of sentiment than substance. Neither side focuses on what scholars call "state capacity": the ability of the state to achieve its goals. Sometimes that requires more government. Sometimes it requires less government. But it always requires a focus on what the state is trying to achieve and what is in its way. In the absence of that focus, absurdity reigns.

This idea, whether the state is achieving its goals, is a central one in the book. Again and again, especially on their press tour for the book, Klein and Thompson stress that liberalism has become overly focused on process over outcomes. Essentially saying, “if we have a robust community engagement process, the public will trust us.”

But this involves adding layers and layers of rules to follow and hoops to jump through that make many projects, like high speed rail in California, impossible. And, shocker, the public recognizes this and actually trusts government less:

"Legitimacy is not solely-not even primarily-a product of the procedures that agencies follow," [Nicholas] Bagley writes. "Legitimacy arises more generally from the perception that government is capable, informed, prompt, responsive, and fair." And that is where government is failing. …

The Pew Research Center has aggregated decades of polls tracking the public's trust in government. The high mark on the chart is in 1964, when 77 percent of the public believed that the government would do the right thing all or most of the time. Confidence plummets from there. In the '70s, after Watergate, it sits in the 30s. It rebounds into the 40s in the '80s and briefly brushes the 60s after 9/11, but the downward trend is undeniable. By 2023 it sat at 16 per-cent. This is not, in our view, attributable solely or even mainly to cumbersome government processes. But the collapse in trust across the same decades that so many processes were being built to affirm that government could be trusted should make us question whether we have yoked the state to a failed theory of legitimacy.

Again and again, the perfect is the enemy of the good. In one passage they quote an affordable housing developer in California. He says that the state, which has an insane share of the country’s unsheltered homeless population, has more requirements on their affordable housing than anywhere in the country, including requiring specially filtered HVAC systems if the development is near a freeway. (Hat tip to Jonathan Robinson from Twitter, here’s an April 2, 2025 RAND report that digs into just how much worse it is building affordable housing in California vs. the rest of the country.)

Klein and Thompson ask: “does it make sense to be asking for special air filtration systems for developments near freeways when the alternative, for many of the would-be residents, is a tent beneath the freeway? To pose the question sounds callous. But to refuse to pose the question, given the need for more housing, is cruel.”

And that’s a private developer who just has to follow normal laws. When the government acts, it has even more restrictions. Heidi Marston, who resigned from the Los Angeles homeless services authority a few years ago and has been a public critic ever since, says that she had a budget of almost a billion dollars but “the money comes with such confined requirements that it’s almost impossible to spend.”

At many points, Klein and Thompson boil their book down to such simple statements that nevertheless help me see these issues anew. Like, wait, shouldn’t the government acting with the full force of the people behind it mean it should be easier for them to build housing, not harder? How have we taken it for granted that the system should work this way??

At its core, Abundance is a call to refocus politics on outcomes rather than ideals, to ask whether the systems we’ve built are capable of solving the problems we claim to care about. It’s not about libertarian rollbacks or New Deal nostalgia. It’s about whether we can make clean energy, housing, and infrastructure actually happen, at scale, with the urgency our moment demands.

I wish these arguments weren’t necessary, but they are

Often when I read these kind of books, which are more about agenda setting than specific wonky solutions and how to operationalize them, I think “c’mon, this is the easy part.” I’m all about “how do you operationalize this?”

I’m also in a bubble, both online and in real life, where these ideas don’t seem crazy to anyone I know. Like yeah, of course NIMBYism is bad, of course we should want the government to be able to build high speed rail and get rid of the barriers to doing that. Kind of a boring book, no?

Well, maybe not as boring and obvious as I’d like. Stepping outside that bubble is a useful reality check and serves as a reminder of how radical these ideas still sound in many progressive spaces.

A friend of mine is wrapping up law school and writing a paper about issues with NEPA, basically the kind of stuff that is in this book. And it’s a seminar so her liberal classmates are reading her arguments and they’re appalled. “How could you possibly be against an environmental law?” A good friend of ours is an environmental lawyer and feels the same way: “who cares if good stuff is being blocked, we can’t take this important tool out of the toolbox that we have for blocking bad stuff from happening!”

It’s a good reminder that these ideas are not commonly held. And that NEPA case is a particularly nice illustration of one of the sharper arguments they cite in Abundance, Nicholas Bagley’s work on proceduralism and the over-proliferation of lawyers in the Democratic coalition.

Bagley wrote about what he calls the “Procedure Fetish,” the idea above that Democrats elevated process over outcomes, in a 2021 piece for Niskanen (following a 2019 Michigan Law Review article). But I do think there’s an almost sociological layer that he adds that is illustrated by the NEPA example above.

Bagley writes:

If America has a procedure problem, it may be because it has a lawyer problem. Among lawyers, anxiety about agency legitimacy is reflexively invoked to defend the legally imposed procedures that structure agency decision-making.

…

But procedures can also burn agency resources on senseless paperwork, empower lawyers at the expense of experts, and frustrate agencies’ ability to act.

This seems to be a consequence of the rising education polarization of society. Most of the highly educated people in the country are Democrats now, a relatively recent trend. So you see legalistic thinking like this proliferate, with a bias towards continually adding new rules and stipulations to solve problems (rather than taking them away).

Implementation is key

One of my favorite sections came later in the book, when they focused on the difference between invention and implementation. They bring up an idea called the Eureka Myth, basically the idea that the hard part is inventing something new, when in reality the hard part is often figuring out how to properly implement, market, and/or scale that innovation.

The chapter weaves in anecdotes from AT&T’s Bell Labs (which invented and marketized a mind-boggling number of things), Thomas Edison, and Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin. Basically, the government needs to be more supportive of this implementation side of innovation.

It’s a great, well-researched chapter that’s been under-discussed in the public discourse about the book. Perhaps a sign, as Noah Smith said, that most critics of this book did not actually read it.

This book mostly focuses on implementation science and as it pertains to hard science, engineering, medicine, those kind of innovations. As well as meta-science, the idea of how we should improve our scientific institutions to make sure they fund the right research and take appropriate levels of risk. Side note, if that topic interests you, I’ve enjoyed Alexey Guzey’s work with New Science on the NIH over the years, as well as Matt Clancey’s work at New Things Under the Sun, and I’m excited to see Open Philanthropy double down on funding this kind of work.

That’s all very important, but I also think an equal focus on implementation is needed in areas of social policy, in large part because “nothing works” and few interventions scale or replicate (a theme I’ve been wrestling with a lot, particularly here and here). Those shortcomings in evidence-based social policy are missing in this book and are worthy of attention for any liberal who wants to increase state capacity. As far as practitioners, I’ve been most excited by Arnold Ventures's work in this area.

As an academic field, implementation science sounds great. “This is how you actually deliver these services,” best practices, that kind of thing. In practice, it seems to be as jargon-y and obtuse and academic as any other field. It’s likely that the field could use a re-boot.

Beware corruption

The push for faster, better implementation and increased state capacity comes with its own trade-offs. There are quite legitimate concerns here that need to be taken seriously around fairness and corruption if this progressive growth and abundane project is going to succeed.

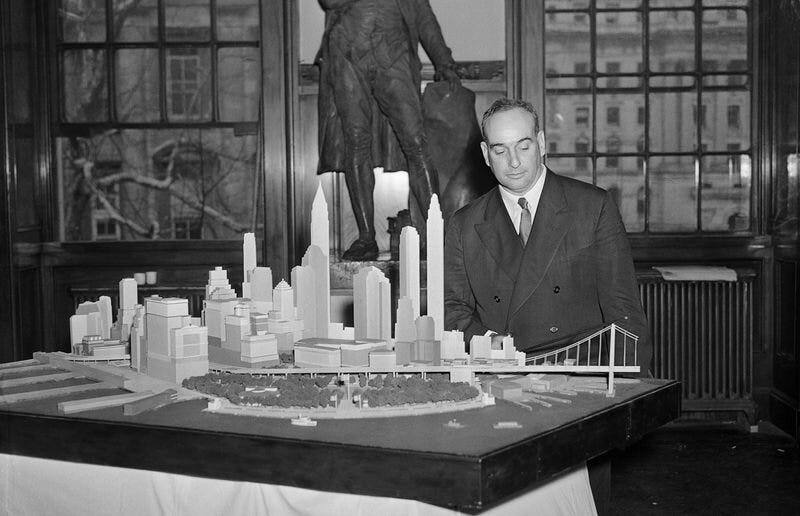

There’s a certain narrative that has solidified among people in the Abundance Extended Universe, including Yoni Applebaum from The Atlantic and others. Basically, the government used to steamroll the public. People often embody this trend in the figure of Bob Moses and Robert Caro’s famous book on him, The Power Broker.

Basically, lots of bad stuff happened when the government became extremely empowered. Famously, Bob Moses and similar Urban Renewal heroes bulldozed minority neighborhoods across the country to build highways.

Eventually, the public rebelled. This trend is often boiled down to figures like Jane Jacobs, who stopped Moses from demolishing Greenwich Village, and Ralph Nader, who sued the government into oblivion in the name of protecting citizens and consumers, were the backlash to this government overreach.

Then, we just took those ideas too far. And now here are the Abundance folks and others to tell us to dial back down some of the restrictions we placed on government so that it can do good things again. Not everyone will be happy with the outcomes in every case, but it’s a better system.

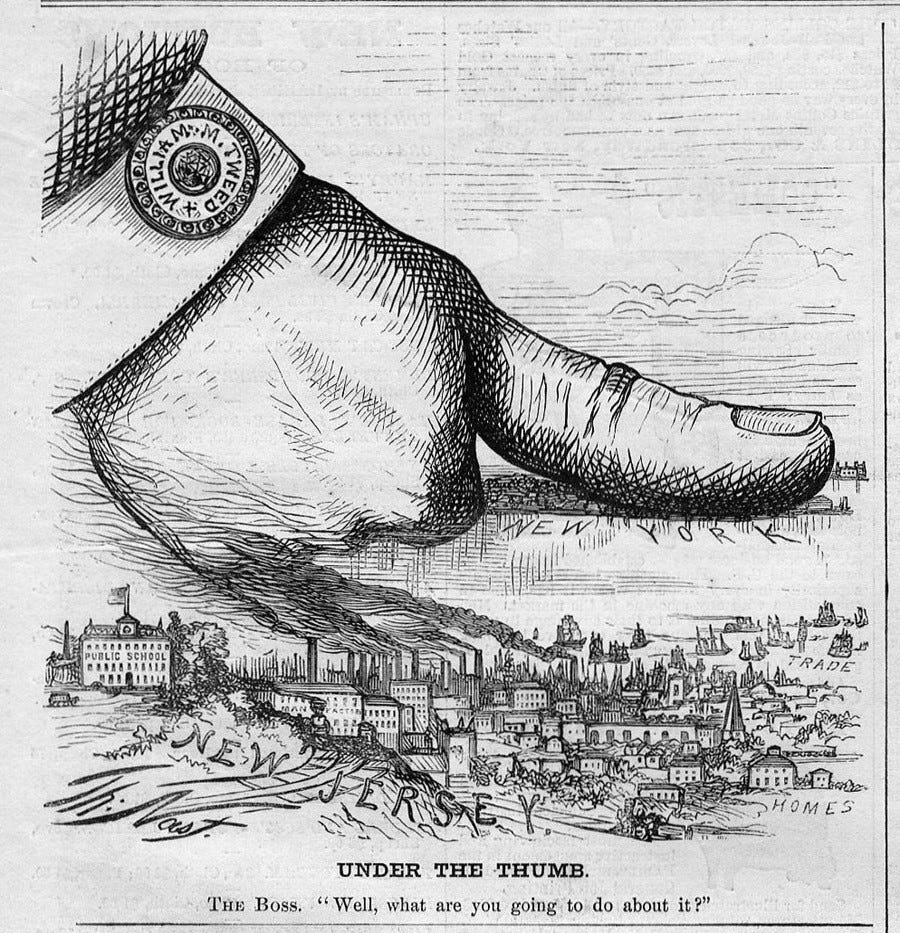

But there is an under-discussed piece of the puzzle here: corruption. This is part of why there’s been a proliferation of processes to reduce corruption in government, particularly among government contractors. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that a lot of big national legislation and jurisprudence that created this status quo came after Watergate.

But corruption concerns don’t map perfectly on to the Bob Moses-centric timeline. In fact, if you read The Power Broker, Moses is initially a hero for leading the way in professionalizing civil service and taking power away from incredibly corrupt Machine Politics. Basically, we’re talking about old school patronage systems (e.g., Tammany Hall in New York) that were often ethnically based.

The corruption stemming from those system led to their own state capacity issues, not to mention the unfair private enrichment of many a grifting politician and contractor. Moses disrupted those systems and stemmed corruption, even though he eventually consolidated power himself in ways that led to the Jane Jacobs backlash. He became corrupt and immune to public opinion in his own way, though it may have been more efficient.

Any system has trade-offs. Klein and Thompson are quick to point that out at a high level. If we let more good things be built, some bad things may get built as well. I know they’re aware of it (see below), but I do think they sort of under-play the corruption angle in the book.

For example, they give the example of the speedy reconstruction of the I-95 in Philadelphia. Governor Josh Shapiro declared a state of emergency and got the bridge rebuilt in 12 days, even using union labor. Here’s Ezra Klein discussing this in a podcast interview with Jerusalem Demsas, describing how Josh Shapiro handled procurement, aka the process of hiring construction firms, on the day the bridge collapsed:

And not far from him are two contractors who are already doing work in that area. And basically, by the day’s end, he has chosen these two contractors to manage the demolition and the rebuild. And he could only do that because all of [the procurement procedures] got waived [due to a state of emergency he declared].

I said, how long would that have normally taken you? And he said to me that the normal way — and here, I’m quoting him — so in a traditional delivery of a project, it would be [12 to 24] months. … And he said, that is probably an underestimate because you’d have to do a bunch of things before you got to that point in the process to even get the process off of the ground.

…

Now, on the other hand, to make the case for process, you can really imagine how, in government — and given our history, or look at any other country’s history with government — if you don’t have pretty rigid rules on who you hire and how, it becomes patronage. It becomes corruption. People get elected, and they give money to their friends, and their friends give them money to get elected. And then you have a corrupt political system.

To cut them some slack, it’s clear from this interview and a few parts of the book that they are aware of this counter-argument and take it seriously. But, in my opinion, backlash to perceived corruption is the real way the Abundance Agenda gets torpedoed. It’s something that the proponents of this approach need to seriously wrestle with.

Now, my opinion is that this kind of self-dealing with government contracting happens anyway. And in fact, adding more and more process may lead to even more of it. The incredible complexity of government contracting means that only really sophisticated firms, probably those with lobbying capacity and the money to get “an in” with politicians, can play ball.

I worked at a foundation, relatively process-light (especially compared to the federal government) and I saw that people who could chat with people that worked at the foundation had a leg up on other applicants. The irony is that the more process you add to combat that fact, the more you reinforce it. At least in a world with simpler government procurement you’d have more competition from smaller, outside actors.

How do you message that politically so that people don’t flip out when corruption is found and blame the whole Abundance agenda? I’m not sure. Maybe the outcomes and results will speak for themselves and thus dull criticism? That’s kind of Klein’s point, and it is what happened with the I-95 example above.

But, as I wrote here, I’m also a bit skeptical of this idea of “deliverism,” that delivering on big policy will make you popular, as often it’s the opposite. People have a strong status quo bias and are scared of change. But perhaps “building new bridges” is apolitical enough that deliverism works.

So where does all of this leave the abundance agenda?

Klein and Thompson are right to reframe the political conversation: not around whether government should be big or small, but whether it can work. Their optimistic tone is smart and creates the basis for a politically-viable agenda.

But delivering on abundance will require more than deregulation and better procurement. It means confronting entrenched liberal political, lawyerly instincts. It means rebuilding public trust, navigating real trade-offs, and being honest about the political risks of change.

I think it would take a charismatic leader who "invests" the Democratic party (in the military sense) and pulls through a new, but resonant agenda over their current morass of contradiction and paralysis. Essentially, like Trump is in relation to the Republican party: transformational (for better or for worse) and unconcerned with ideological legacy.

Will that providential person show up? Don't know. I'm not seeing anybody with enough brass on the horizon.

I haven't read the book and I wonder whether the authors are brave enough to address the fundamental problem of American "Liberalism" (capital "L"): which is that it is founded on and structured by guilt. Essentially, Liberals are mostly white people who feel guilty towards black/brown people (less so towards Asians, never towards Jews), men who feel guilty towards women, straight / cisgender (fka "normal") people who feel guilty towards the alphabet ones, etc. In turn, the objects of their guilt, when organized, exploit it relentlessly in the form of handouts and moral blackmail for its own sake.

This happens to lead to specific forms of corruption (see two recent scandals involving black / women-oriented advocacy in SF brazenly bilking taxpayers), because it would be *unconscionable* to demand any accountability of these deserving minorities.

More importantly for the "abundance" agenda, the inverted moral pyramid of "Liberalism" puts the avoidance of harm to hallowed minorities (or environmental "causes" embodied in some charismatic weed or critter) at the top of social priorities. As a result, nothing can be built that could ever ruffle the hair of a black or brown person, or disturb some rare vole etc. And since *any* building project will *always* find a way to involve, and in the short term make worse off such people or things, then...nothing can get built, ever. For instance, the California coastal commission nixed the building of a much-needed desalinization plant in the Long Beach area, because - wait for it - it would make drinkable water more expensive to nearby black residents. That's California for you, but since the state is a byword for Blue-state dysfunction, the example is relevant.