Why care about politics if nothing works?

An attempt to escape nihilism in a world of policy failures

I’ve been grappling with the findings summarized in my piece about how “nothing works.” It’s left me wrestling with a dilemma: If most policies don’t work as we expect, what does that mean for how we should approach politics and policy change?

I’ll begin by revisiting Stevenson’s findings and their implications for policy change. Then, I’ll examine two Missouri case studies—Medicaid Expansion and Clean Slate—to explore how these ideas play out in practice. I’ll then consider broader lessons about the role of narrative change in politics and end with an appraisal of incrementalism.

Stevenson’s challenge

Megan Stevenson’s analysis of decades of randomized control trials (RCTs) reveals that most criminal justice interventions, from job training to modified probation, fail to produce lasting or scalable effects. This aligns with the “Iron Law of Evaluation,” which posits that the expected net impact of large-scale social programs is often zero. Stevenson attributes these failures to structural forces she calls “stabilizers,” which resist externally imposed change, and critiques the “cascade” model of social change, where small interventions are assumed to create ripple effects throughout a person’s life.

Interventions premised on that kind of cascade effect are particularly unlikely to scale or work when rigorously evaluated. The main example I used in my piece is a re-entry job program: if we give someone fresh out of prison a job for their first six months, they’ll be more likely to have a job, be stable, and not re-offend in the next 5 years. Unfortunately, not true.

Given these findings, Stevenson offers three responses: focus on direct interventions that work while they are being delivered (e.g., feed the hungry with no expectation of a ripple effect); embrace uncertain incrementalism, accepting small, hard-to-measure gains; or pursue ambitious systemic reforms that address structural forces on a broad scale.

After wrestling with Stevenson’s piece and a Niskanen/Vital City symposium of responses, I concluded that some interventions do work, it’s better to change someone’s incentives than to try and change their preferences (hat tip to Alex Tabarrok’s response), and systemic reform is more likely to create durable change.

But the devil is in the details and I’m left wrestling with some fundamental questions about politics. You can’t always be swinging for the fences in the political arena, you have to focus on smaller wins along the way. But many of those smaller wins are the exact kind of policy changes that the evidence says usually don’t work. This left me feeling somewhat nihilistic, so this is my attempt to write myself out of it.

Two Missouri examples: Medicaid and Clean Slate

To illustrate the spillover benefits of organizing for policy change, I want to return to an example from my last post about Medicaid Expansion. For those who don’t know, Missouri is one of the states that chose not to expand Medicaid to low income people after the Supreme Court said that piece of the Affordable Care Act was optional. It took around 10 years of grassroots effort, but eventually Missouri expanded Medicaid via a statewide ballot initiative. Here’s what I said in that previous piece:

In states like Missouri where it took a 10-year battle post-ACA, there was real organizing that took place that shifted voters’ understanding of politics. People were persuaded that we have a shared responsibility for the health of the poorest people in the state. That is a big mindset shift and may mean that even if Medicaid changes, the state will still need to care for poor people some other way. That’s a profound shift for a conservative voting public, and likely more impactful in the long term than the Medicaid expenditures for a given year.

Medicaid Expansion does seem to work and save lives, albeit at a much smaller effect size than some expected. But again, the primary benefit may be the change to public discourse that will continue to define future policy fights.

But let’s take the findings that Megan Stevenson summarizes seriously and ask how we should think about this if we’re fighting on behalf of a policy that we have less evidence works. That is most policy areas. With Medicaid Expansion, the best evidence didn’t even emerge until after the ACA was passed and we spent billions of dollars on it:

Recent developments in the literature on the mortality reductions achieved through health insurance demonstrate this problem. While, as Stevenson points out, pre-Affordable Care Act studies, including RCTs, generally found no effects of health insurance on mortality, two rigorous studies conducted after the insurance expansions (using different methodologies) — one examining Medicaid expansions and the other focusing on private insurance expansions — found convincing evidence of mortality reductions. They looked at samples of over 4 million people and nearly 9 million people, respectively. The enormous samples allowed them to identify effects that were relatively small in percentage terms (although they translated into many thousands of lives saved annually at the national level) and to home in on the subpopulation over 45, where baseline mortality rates from health care-amenable interventions are higher than among younger adults. But that kind of opportunity for identifying policy effects of modest size doesn’t happen very often.

So that means that the whole ACA fight, one of the biggest systemic political reforms of the last 20 years, which spent down most of Obama’s political capital for his entire eight years in office, was premised on an idea (giving people health insurance will save lives) that didn’t even have robust evidence behind it!W

I’ve got a more recent Missouri case study: Clean Slate. It’s a campaign from Missouri nonprofits to pass an automatic expungement law. It’s a useful example because I know and respect many of the people involved in this campaign and I’m completely value-aligned on this issue.

The idea is that expunging people’s criminal records makes it easier for them to get jobs and find housing. This eases their reentry process, which in theory should have a cascade effect. If they manage to get a job and housing, they’re more likely to hold those down, reintegrate into society, and thus less likely to commit crimes and end up incarcerated again. Here’s one of the bullets from their fact sheet:

Notice that this is reliant on the exact kind of “cascade theory” that Megan Stevenson says basically never works out in practice when we get high quality evidence. I’ll also note that there’s a similar reform, called Ban the Box (which bans employers from asking about criminal history). The evidence from those reforms is not the most promising, with one study finding that employers compensate for the lack of information by stereotyping applicants. As a result, they end up discriminating more against black employees, who they see as more likely to be criminals.

Overall, the literature is mixed. At best, the jury is out on whether Ban the Box works, as well as how serious the racial discrimination trade offs are. In line with Stevenson’s research, I think we should just assume it all nets out at having zero effect until we learn more. And I’d say we should assume Ban the Box and Clean Slate likely have similar effects.

So does that mean it’s a waste of time for Missouri groups to push for this reform?

I don’t think so. I think that, similar to how Medicaid Expansion provided an opportunity to persuade voters about our shared responsibility to provide healthcare for the poor, Clean Slate provides a useful opportunity to have similar conversations about how we should view the formerly incarcerated. I love this issue framing from their website:

If organizers are able to get this passed via the legislature or the ballot, it would involve changing people’s minds about how to deal with people who have committed crimes. Instead of seeing criminals who are forever defined by their actions, they can see hard-working people who we want participating in society and want to help on that journey. This shift has already begun, as Missouri passed an expungement law before, but it required people to fill out paperwork and has tons of barriers so effectively no one uses it. Passing automatic expungement would help cement this new way of treating and viewing the formerly incarcerated.

In other words, the actual policy and its impacts may not be that important. The bigger win may be changing hearts and minds.

Narrative change is important, but how you do it is more important

But here’s where it gets complicated: the policy victories we’re discussing aren’t just about practical outcomes—they’re also about shifting mental models, framing issues in a way that changes how people think about them. This brings us to the idea of ‘narrative change,’ a hot topic (along with “mental models”) among funders, which I think is crucial but often misunderstood.

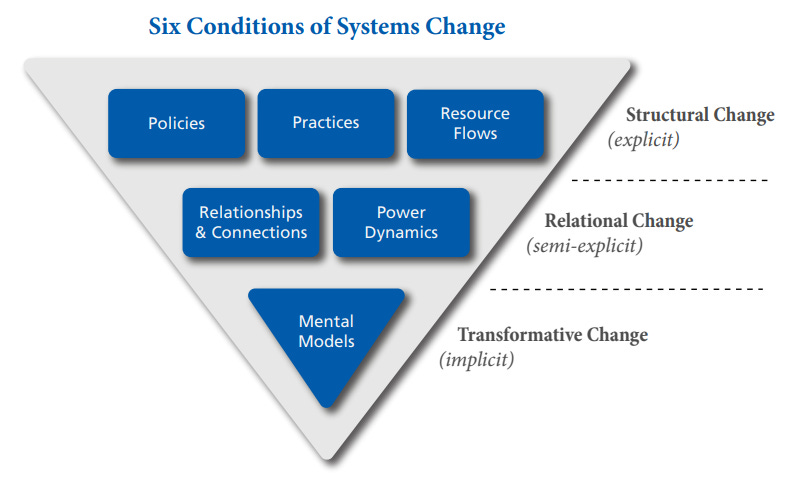

Shifting mental models is often discussed as the “deepest” form of systemic change you can make and thus highly desirable. Here’s an example of this framing from FSG’s Water of Systems Change report:

To break that diagram, we’re talking about the “systemic reform” that Megan Stevenson outlined. Think of this almost like an iceberg (another common model that systems change thinkers use), where the explicit and semi-explicit are closer to the surface, but the mental models are what lies underneath the surface.

I believe that people who focus on narrative change and shifting mental models are picking up on something real, as I said above. Changing hearts and minds is important. Nevertheless, funders and nonprofits often make some mistakes trying to operationalize that assumption:

People often focus on art and media divorced from the material world, regardless of the impact or audience.

For example: funding a local artist whose work is seen by <100 people.

Often a micro-level focus on language is the goal of this kind of work, rather than a material policy change

For example: getting people to stop saying “illegals” and instead say “undocumented immigrants” vs. passing a path to citizenship.

Both of these are based on reasonable ideas, but I think err when they are too disconnected from a material policy fight or concrete actions you’re asking people to take.

For the first one, it’s true that art does have some degree of impact on public discourse. But it’s also true that what changes public opinion is a show like Will & Grace, which famously helped normalize homosexuality. A sitcom with a very stereotypical gay character is not the kind of art that foundations are usually funding (to my knowledge), they’re focused more on political art, journalism, and documentaries. Sure, sometimes a documentary like Blackfish goes viral and starts a broader conversation, but that’s rare enough that you shouldn’t plan a strategy around it.

As for #2, I do think language shifting is important, but I don’t fully buy the theory here. The idea is that if you get people to speak “more humanely,” they will then become more humane in their policymaking.

This is based on the idea that the only reason that people don’t want to do your preferred policy is that they are inhumane and lack empathy. That may be true to some extent, it is important to educate the public about the impact of policy issues, often via storytelling. But politics is also based on pretty fundamental questions of values, culture, and tradeoffs that don’t go away just because you substitute one noun for another or read a sob story.

In my opinion, the actual language win you want is something more like what the Clean Slate campaign is doing. They’re framing a progressive issue (treat ex-cons better) in the value system and vocabulary of conservatives (economic benefits of successful reentry).

That’s how you actually get bipartisan wins that benefit the formerly incarcerated, not by shaming conservatives out of calling them “felons.” And again, you’re having the conversation in the context of a concrete policy decision and asking people to take specific actions. You’re not just talking in the abstract.

But why care about politics if policy often doesn’t matter?

This is kind of the inverse of how people typically think about politics. Policy changes are supposed to be the goal, they’re supposed to actually accomplish things and make people’s lives better. But if we assume that many policies do nothing (or backfire), it becomes more about the journey, the mental model shifting, the friends we made along the way.

But I think that would strike lots of people as hollow, and it’s a hard base to build a movement on. “We need to run around pretending that this likely-ineffective policy matters so that we have an excuse to talk to people about the issue” is much less motivating than “we need to convince people to pass this life-changing policy!” Even though I think that a clear-eyed look at the evidence suggests that the former more accurately describes the political process than the latter. What to make of this?

First, a caveat. As I mentioned in my previous piece on this, some things do work. We should feel pretty good about straight-up redistribution and some public service delivery. If you give kids free school lunch they will, in fact, be fed. They may be no more likely to be healthy at age 30, but who cares? Feed the damn kids!

And there are policies like Medicaid Expansion that do have strong quasi-experimental evidence behind them. Though that one is complicated, because like I said above we likely did not have the evidence at the time of ACA passage to justify that big of an expenditure on health insurance expansion. Maybe the theory behind it was just that strong.

But we should be realistic that the list of policies that we can be confident work is much shorter than anyone wants it to be. Again, this is as true for conservative policy goals as progressive ones. So then what’s the goal of politics?

For my social movement friends, the type working on Clean Missouri, it’s all about building power and a broader movement over the long term to fight for bigger and bigger wins. It’s all about sticking it to the powerful and using that sort of populist appeal to knit together a working class coalition to achieve..

To achieve what? More policies that are by definition less likely to be possible now, so we probably have even less evidence behind them? That last part is where I struggle with nihilism or maybe laissez faire conservatism

Some of those friends of mine are socialists, so they see a more radical transformation of the American economy as their ultimate goal. I can’t really get on board with this for two reasons:

I’m not a socialist anymore, in part because it feels like a really hazy end-point. It’s a lot of vague goals, but also denying all of the counterexamples where those goals didn’t work out in practice. I’m left not even sure what I’d be co-signing if I called myself a socialist.

I’m increasingly feeling the pull of Burkean epistemic humility. In other words, we need to have more humility about unintended consequences, particularly of big policy shifts. The bigger the goal, the less confidence we should have in our ability to predict how it’d work out. If we can’t even predict that a successful DUI-reduction program in Hawaii will also replicate in Oregon, how am I supposed to get on board with “transform the entire economic and political system” as a goal? So if we skip the issue with #1 above and get more specific about the end-point, I then lose confidence.

I’m picking on the socialists because I’m left-of-center and they’re my friends, but this isn’t unidirectional. I feel similarly about the more libertarian right-wing people. Nevertheless, it is these kind of zealous political thinkers who often end up engaged in movement work. This is likely because it’s really hard and you need to have lots of passion to keep the fight going.

So for some people, the reason to push for policies even when we don’t know if they’ll work is to raise the salience of particular issues so we can knit together a movement towards broader, longer term goals. I may struggle with the “longer term goals” part of that, but it’s a coherent theory.

I actually think if I substitute “narrative change” in here it makes me feel a bit more comfortable, as I may be able to get on board with the long term goal of “destigmatize someone who served their time in jail and is making an earnest effort to re-enter society” even if I may not be on board with full on prison abolition, which I’m sure at least some people advocating for Clean Slate see as the long-term goal of power-building here.

Maybe it’s all about muddling through

As I mentioned in my summary at the top, Stevenson offers three approaches: focus on direct interventions, embrace uncertain incrementalism, or pursue ambitious systemic reforms that address structural forces on a broad scale.

Initially, I enthusiastically embraced the “ambitious systemic reforms” approach. But the more I sit with it, the more I think that incrementalism offers a better way out of the paralysis induced by Stevenson’s findings. It’s not about abandoning ambition but about balancing it with humility and learning through smaller steps.

Charles Lindblom’s concept of “muddling through” offers a framework for reconciling the tension between bold systemic ambitions and the limited information we have about what policies work. Incrementalism isn’t just a compromise; it’s a pragmatic acknowledgment of our inability to fully predict the consequences of sweeping reforms. By focusing on small, iterative changes we can test, learn, and adapt—avoiding the hubris of assuming we know exactly how to solve complex societal problems.

Part of the benefit of an incrementalist approach to politics is the “laboratories of democracy” idea. What we should learn from Stevenson’s work is humility. Taking smaller bites at the apple, taking time to see how they go, and then adjusting (or scaling a great idea out to other places, but continuing to evaluate it when we do) is a feature, not a bug of how our system works.

But in order to learn, we need to embrace more robust evaluation and at times funders need to force nonprofits to think in those terms. I’ve been particularly impressed with the work I’ve seen from Arnold Ventures on that front. Nonprofits and funders alike have become too dependent on anecdata that reinforces an echo chamber, or leading poll questions intended to show greater support for your cause than actually exists. And, to tie all of my recent posts together, that contributes to the messy epistemic environment that Democrats are in and their unhealthy relationship with The Groups.

Policy successes in the future may be to prevent the privatization of public services and benefits. So Burke is on your side. Let the Republicans prove the harmlessness of their policy proposals with RCTs