Is there any hope for The Groups?

Unions, organizing, and post-post-election thoughts.

I’m continuing to process the election with friends and family and reading the coverage of various pundits, mostly centrists. I’ll continue to develop a few of these points here and highlight some perceptive stuff I’ve read.

What’s up with The Groups™?

As I reckon with the thesis that Democrats have become too extreme on too many issues at once, I find it hard to reconcile the influence of The Groups with their lack of real power. But it does seem to be reported again and again. Here’s Ezra Klein in one of his recent podcasts (he’s been on a tear lately), interviewing Michael Lind. He’s talking about how environmental groups killed permitting reform that was needed to help move decarbonization efforts forward:

The Biden administration certainly wants to build as much green energy infrastructure as fast as it can. And I’ve done a lot of coverage of the way that permitting and procurement and land-use rules and environmental litigation and legislation have proven to be real obstacles in Democrats building fast and affordably. You have example after example of major energy projects being stalled in environmental litigation, getting sued because this thing that will build a huge number of solar panels and create a huge amount of solar power could conflict with an endangered species or some other set of laws. Even if really just what’s happening is these laws are being wielded by people who don’t want the thing in the first place.

And so I was covering and watching what was happening in Congress as people tried to grapple with this and tried to think about on the Democratic side what permitting reform might look like. And when I would talk to the people working on it, I was just stunned by the power of small groups, environmental justice groups, and so on, that didn’t really represent anybody, or at least not any large numbers of people.

They would just explain to me that if you couldn’t get them on board, they couldn’t move forward with this at all. And I would say, “Well, what is the power of these groups — like, what is their leverage on you?” And there was never an answer. It was just a coalitional decision that had been made in the culture of the way the Democratic Party now made policy.

It wasn’t that somebody thought they would turn votes on them. It wasn’t even anybody thought that one version of this would be more popular or even more noticed than another. It’s just that a culture of how you make policy had emerged, a culture of who you listen to had emerged. And it couldn’t be broken, even if that meant a genuinely smaller chance of achieving a goal that you believed and had told everybody else was existentially important: the speed of decarbonization in the coming 10 years.

And I really began to understand it as that. This is probably where I departed from the version of this calling it a machine. It seems like a culture to me. Not a culture sort of built on anything. It’s a culture built on norms and practices, not exactly on leverage.

That cultural explanation has felt like it's missing something. I’m someone who often favors more structural, incentive-related explanations for things. But there does seem to be something here in the cultural thesis. Here’s Ezra again on Pod Save America, highlighting the way that there’s a revolving door dynamic here that contributes:

So I’ve been thinking a lot: what in God’s name was the ACLU doing giving Democratic candidates in 2020 a written exam asking, among other things, are you supportive of providing gender reassignment surgery to undocumented immigrants in prison? Right? Writing this edge case madlib about the most unpopular policy one could possibly imagine. There’s another question: what were the Democrats doing answering that? Which Joe Biden, to his credit, doesn’t! He leaves it blank. But one thing that’s worth saying is that a lot of people working for these campaigns, Harris in particular comes out of the legal wing of the Democratic party. The ACLU: if you look at the legal establishment, the connections to the ACLU are very deep. Many of them have worked there, they go back and forth there. Having your friends at the ACLU be mad at you doesn’t feel good. Aside from anything else you might think about them, these are social networks. … Did the ACLU think it was helping trans people when they did this? Because it wasn’t. Helping to raise this up as an issue that helped defeat Kamala Harris in 2024 and helped elect Donald Trump. What was the ACLU doing here? What role did it think it was playing by coming up with this edge case and getting Democrats to say on the record they were for it?

Just because I think he’s been on a tear lately, here’s Klein on one last point from that same Michael Lind interview above, on the sense in which this culture has produced an environment where everyone’s roles have become mixed up:

There is a conflict I think about sometimes some years ago between Obama and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. And it had to do with Obama criticizing activist tactics, which he did quite a bit. And this is postpresidency for him, and AOC making this point that not everybody’s job is to be within the Overton window: that activists have a different job than presidents, than politicians, etc.

But on the other hand, the implication of that point was that Obama was doing exactly what he should have been doing, even though this was being used as a criticism of him. That if everybody has different jobs, then actually it is the job of the politicians to hold the line at where the politics net out for their side.

Because as you say, the nonprofits are — and as AOC said — the nonprofits are not there to win 51 percent of the vote. But the politicians are. And I think this goes to the coalitional dynamic that you’re describing, and I saw this a lot covering policy in the last couple of years, where when you weave in the nonprofit complex into the official party, people are moving between it — all the time. Going from the administration to the nonprofits and nonprofits to the administration. Members of Congress are bringing in these groups every time they’re doing legislation and sort of taking their temperature and the coalitions really matter and you’ve got to stay on the side of the coalition or they’ll get mad at you.

And then you’ve mixed up people’s roles. And, by the way, I think that’s a Twitter thing and a social media thing, too: where people who used to operate in quite different spheres of politics were endlessly thrown into one conversation together — collapsing the roles between activists, between politicians, between media figures, between political scientists, between grass roots organizers, between donors. Like, everybody is in the same discourse level, acting as if they’re doing the same thing — when they’re really not.

The fact that Twitter and the Internet more generally have put all of these people in touch with each other, ostensibly on equal footing and with a public audience, is another useful point to understand how this culture emerged.

Well, hopefully some of these norms and practices are in the practice of shattering. I wonder what the internal conversations within the ACLU National office are like right now.

What is a Group™ to do?

One of the obvious reactions to the excess influence of The Groups is for elected officials to just stop listening to them on everything. Perhaps we just lived through this weird Twitter-mediated fever dream where everyone forgot their roles and now we’ve all been rudely awakened. If the ACLU tries to ask candidates in the 2028 primary their stances on edge cases again, my guess is most (if not all) candidates just decline to answer or maybe even ignore the ACLU entirely. Similarly, I doubt we see another 2020 primary in 2028 where all the candidates try to out-flank each other to the left, though I do still worry about that because of how partisan primaries work.

But if you agree with The Groups about issues (some of which I do, some of which I don’t), that probably feels unsatisfying. Isn’t the point of being a progressive to move causes forward?

First, I think people need to burst their bubbles, leave their echo chambers, and anchor themselves in real public opinion. I hope this election (and the electoral trends over the last few cycles) put to death the myth that there’s a Silent Majority of disengaged voters who agree with Democrats about everything and if we just drive high turnout we’ll win. I associate that view largely with the 2016 Bernie campaign and Stacey Abrams since then.

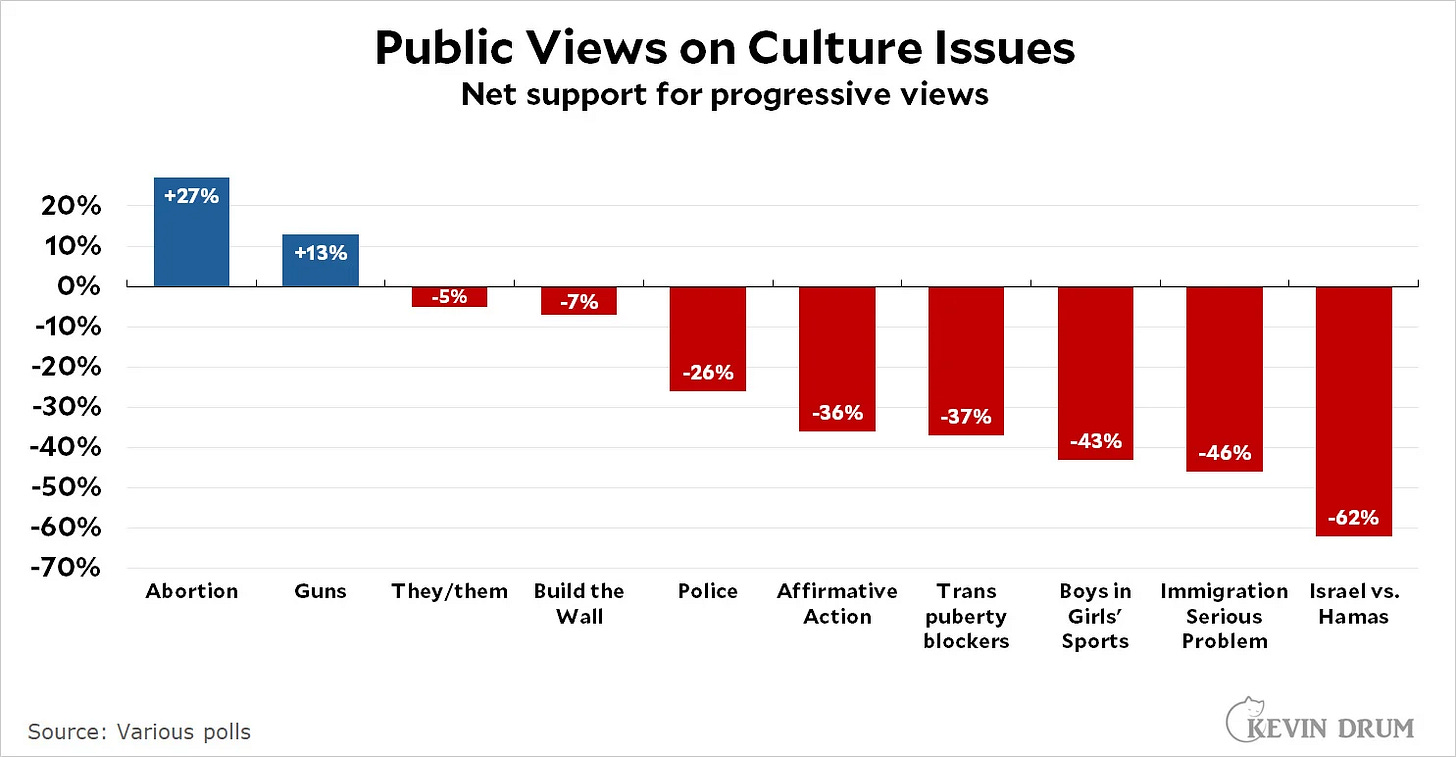

To start with culture wars issues, Kevin Drum had a good recent post where he graphs the current state of public opinion on a handful:

Okay, now we’ve got clear eyes. And, like the 2024 election result, that’s kind of depressing to see it all graphed like that, even though you can quibble with the crude framing of some of these.

Sorry to break it to The Groups, but if (1) public opinion isn’t on your side on an issue and (2) politicians remember that they don’t need to listen to you on unpopular issues, then you can’t just go with elite persuasion via Twitter guilt and giving mean quotes to the New York Times.

They’re probably now back to having to do real organizing, build real power, and actually persuade the American public about their positions. It’s not like politicians will never take issues that diverge from the American public’s views (Democrats prioritized climate action far ahead of public opinion in the Biden admin, which I think was great and important), but it’ll be more of a consideration, particularly on the cultural issues that Democrats get attacked on again and again.

Now, I’d be bummed about this if I was a progressive advocacy nonprofit. It was a pretty sweet deal post-Obama to just get a grant from a foundation, publish some reports, take some photos of a rally that has 20 people at it (half being your staff) with an angle that obscures the true crowd size, yell at someone on Twitter or occupy their office in Congress once, and then get their progressive staffers to sign on for your pet cause.

But it is possible to still get stuff done! Similar to how smart Democrats are looking to successful swing state governors and Democratic Reps who won in Trump districts for lessons, I think progressive groups should look to their colleagues working in red states for lessons.

Progressive wins are possible, but it does involve real organizing and power building. Which, guess what, will also bring you back into contact with some of these working class and disengaged voters the Dems are losing. And if you talk to them, you’ll learn quickly that those voters don’t speak about these issues the way that the ACLU does.

To talk to those people, you can’t talk like a progressive academic jargon robot. And the same applies to speaking with Republican legislators and officials. It is possible to articulate progressive views in the value systems and language that resonate with conservatives.

I know that I’m sounding like a sellout centrist moderate (which I am), but I promise, winning feels great! I think the useful part of this kind of post-mortem moment is that everyone is very attuned to how bad losing feels.

What should these organizations look like instead?

As we talk about progressive organizations building real power and connection to unify working class people and connect them with electoral politics, it’s sure starting to sound familiar..

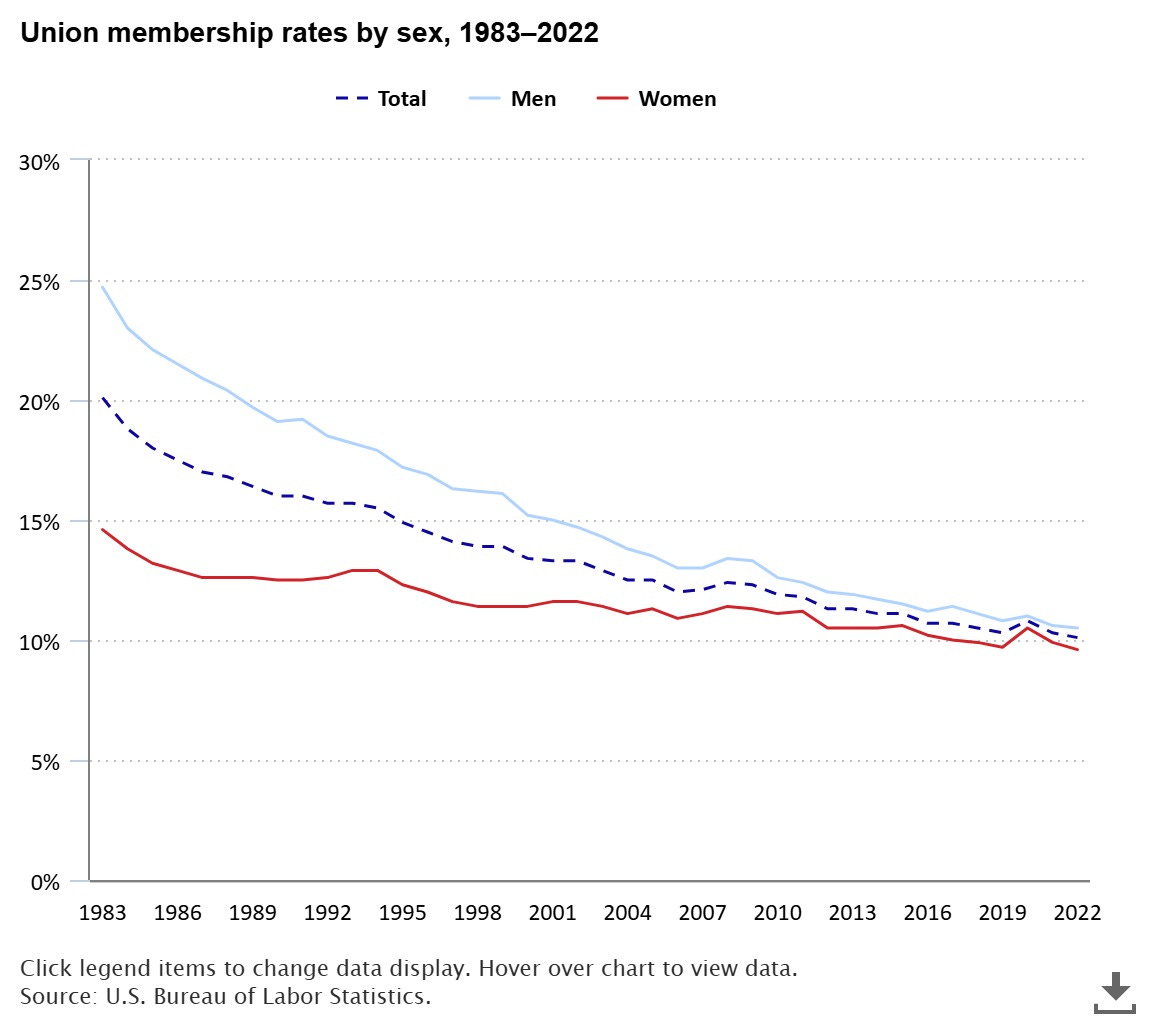

In fact, it’s reminding me of the Conclusion/Solutions section of every progressive political book I’ve read over the last 10+ years, which always feature Rebuild the Union Movement as one of its solutions. And for those who don’t know, in 1954, 35% of workers were in unions and here’s the trend in union membership over the last 40 years, courtesy of the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

But more abstractly, we’re talking about membership organizations. Dues paying, democratic, federated organizations that level up to the national level. Each of these pieces are important. Dues paying means your members have skin in the game and the organization is not dependent only on outside grants and appeals to wealthy donors. Democratic means that these dues paying members actually shape the organization’s priorities, ideally creating some connection with lived experience of normal people who don’t all work at nonprofits and have college degrees. And federated means that you have smaller chapters that can negotiate with each other about what their higher level interests are, and then transmit that to some national office in DC who can talk to politicians.

There used to be tons of these in America about different issue areas, as well as fraternal organizations that were largely for fun but sometimes engaged in politics. Early this year I read Theda Skocpol’s Diminished Democracy (2006), which told the story of the decline of membership organizations and warned of some of the dynamics we’re seeing manifest now, where foundation-funded member-less organizations have taken the place in national politics that used to be held by actual member organizations. In some ways the culture Ezra Klein describes above is Democrats hallucinating and mistaking member-less organizations for membership organizations. Or perhaps the public mistakes that, which drives politicians to be cautious about crossing them and getting a bad quote in the press.

I’ve been meaning to write more about the Skocpol book for awhile, this election is probably a good push to do so. But, in brief, she (1) highlighted how membership organizations played a critical role in socializing people and building power/networks across class, and (2) correctly warned about the consequences of a shift in power from membership orgs to philanthropy-funded advocacy organizations.

Do unions even work this way?

Okay, let’s say Skocpol is right and the problem with The Groups is that they’re disconnected from working class people and the Democratic Party would be better if it were influenced more by Groups with real power instead of hollow foundation-funded ones.

It’s worth questioning the premise that even the still-existing traditional membership organizations (1) have real power over their members and how they vote, and (2) delivering on material issues for them will influence those votes.

There are, in fact, still unions in this country and they are not all behaving this way. Biden did an unprecedented bailout of the Teamsters Unions’ pension fund and they still would not endorse Harris. They were officially neutral and their membership was deeply pro-Trump. Their president even addressed the RNC, despite no real track record of pro-labor policy from Republicans!

I don’t want to over-extrapolate here from one union, as the Biden admin also did labor-friendly tariffs and industrial policy and did secure the endorsement of many major unions like UAW. But let’s look at union members, who are about 60% Democrat, 40% Republican. That’s not bad for Democrats, it’s about 10% more Democratic than the non-union population.

I tried unsuccessfully to find historical data, but I’d bet that union support for Democrats was stronger in previous political eras. And it’s a far cry from the 77% support for Harris among Black voters. That’s what a core coalition member looks like (though that strong connection with Black voters also seems to be gradually fraying). In short, Democrats are still getting some electoral benefits from unions, but it’s not as much as I would have thought.

For comparison, let’s look at education polarization, where the clear dynamic has emerged that college graduates lean more and more Democratic and non-college graduates lean more and more Republican. Despite all the ink spilled, those numbers are not as tilted as the union ones, with 56% of non-college grads voting for Trump and 55% of college graduates voting for Harris. Asterisk: these are exit poll numbers, so it’ll be worth re-examining in a few months once better data is available.

But the problem is the denominator: there just aren’t that many union members anymore. About 11% of Americans are in unions. In elections where the margins are razor-thin, maybe you do want to win 10% more of 10% of the electorate, but you certainly need to start questioning how high a priority that is.

But more than that, you need to start asking a different question: if there’s a case study for how membership organizations should work in 2024, this is it. You’ve got material issues, related to one of the most high-salience issues in one’s life: where you work, how much money you make, whether you can retire with your pension. The policy work is targeted at traditional membership institutions (unions) that are specifically designed to influence policy and filter information back to their members to move their voters in turn. And all that policy work was not enough to keep from losing voters in those organizations.

Why don’t membership organizations work this way?

I’m surprised at that outcome. I’d like to offer a few possible explanations for why membership organizations don’t work the way we expect them to, and why it’s so hard to get the kind of true organizing work off the ground to create functioning membership organizations.

#1: We’re in a post-material world

Another way to put this: maybe people care more about culture wars issues than they do about the bread-and-butter material issues that used to drive politics.

The Teamsters Union example is a great one. I think it’s a totally valid theory of politics to say: if I bail out the Teamsters Union, a union member will hear that, go “wow, that’s amazing, my retirement plan is saved! What could be more important to me than my own retirement?” and vote for Democrats.

But what we just saw is that theory doesn’t actually hold true in the world. So part of that logical model must be wrong. My guess is it’s at least in part about what’s important: I think we’ve seen in practice that working class people are weighting cultural and aesthetic (more on that in another post) issues higher than traditional pork barrel politics.

#2: Organizing is too hard

Lots of people call themselves organizers, especially community organizers, but there’s a pretty wide spectrum of activity that goes on under “organizing.” Political organizing is different, since you aren’t working to build the kind of long-term, durable power and base that is required for the kind of membership organizations we’re talking about. Your relationship with voters is more limited in scope, time, and depth.

In my experience, the people who do some of the most serious, long-term, durable organizing to create real membership organizations are in the labor and union world. Some of my best friends are labor organizers and after college I almost went into the field to work for somewhere like the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

But I didn’t because the work hours are insane and work-life balance is almost non-existent. If you’re organizing working people you need to be available on evenings and weekends. To do organizing well, you often need to drive out and meet people in their homes and/or drive workers around to events because of their own unreliable transportation. My friend who’s an organizing director has put more miles on his car in 2-3 years than I have in 10.

And that’s just the time commitment. Not everyone can be trained to effectively speak with a high volume of workers at a high quality, with fidelity to the sort of evidence-based conversations that move organizing forward. Talking with my friends, I’ve heard many stories of smart people who just can’t cut it in organizing or aren’t open to the kind of coaching that’s necessary to move from personal charisma to hard-nosed, disciplined organizing.

I’ll note: this explains why it’s hard to get new membership organizations created (and why unions are declining). But it’s also part of why organizations like the Teamsters struggle to move their members after they extract policy wins. You don’t just need to do organizing to bring in new members (which is called external organizing in the labor world), you also need to organize your members to take particular actions, like vote for Democrats because they bailed out your pension fund (which is called internal organizing).

Now, let’s put the skill issue aside. Some people are workaholics. Plenty of them work in politics. So maybe a critical mass of those people can shift their always-on-their-work-email focus and energy towards non-political organizing instead. But, frankly, I doubt it. It’s really hard, grueling work. As much as highly educated progressive people want to talk on a panel about working class people, they don’t actually want to talk to working class people. They’ll tolerate it in door knocking for a ballot initiative, but do they want to spend years having long, kitchen table conversations with Walmart warehouse workers? That’s what’s required to build a movement.

I’ve shared this concern with the people I know who are doing this work at the highest level. They amaze me, but I just really doubt that we have enough of them to scale this kind of work.

#3: People are too comfortable

This is related to point #1, but it’s slightly different. I’m thinking about what happens when an organizer goes up to a person working at Walmart hauling shopping carts and tries to organize her into a union based on material issues.

Let’s say that Point #1 doesn’t apply, and that worker does rank her material issues pretty highly. She’d love higher pay, she’d love a longer break, she’d love paid sick leave, she’d love better support from Walmart if she sprains her ankle on the shift one day. She doesn’t really care about all these culture wars issues: who cares what bathroom her coworkers use?

A brief, but related tangent. I don’t think we have a serious risk of a civil war in this country. I think we’re all just too comfortable. Maybe there will be more Cliven Bundy-esque1 resistant militia groups (and not just right-wing people, I just read Days of Rage about left wing militants in the 1970s) but what critical mass of Americans is going to go shiver in a wet, muddy tent every night while they tend their gangrenous wounds and eventually die face down in a trench? People will just post on prepper gun forums or Instagram-story their Marxist-Leninist memes and then go back to watching Netflix. The delta between the brutal, tough, impoverished home lives that many Americans were living in the 1860s and the reality of war is so much smaller than that delta today.

Maybe it feels like an attenuated comparison. But that higher standard of living, combined with the Bowling Alone-esque atomization of society, is part of why organizing is so hard. Not only are people comfortable, but the muscle of participating in Tocquevillian associational democracy (essentially the kind of robust membership organizations that Skocpol wrote about) is just too atrophied. The activation energy required is higher and people are more comfortable not spending that energy.

“I’m going to go out and really protest” or “I’m going to spend all every Wednesday night in an organizing committee meeting for my proto-union” were just smaller asks in previous eras of American history when everyone went to Church, was in a guild or union, belonged to the Elks Lodge/Free Masons/local VFW, and maybe belonged to a Temperance Society or Women’s Suffrage group. If someone approached you about joining another group it wasn’t some weird outlier in your life, it’s just what people do.

The Walmart worker example above is about unions, but I think if anything the headwinds are even worse when it comes to other issues you’d try to organize people about. After all, what takes up more hours or has a greater material impact on your life than your job? If we see challenges in organizing people and getting them to commit to concrete actions like volunteering their time or paying membership dues for that, how in the world are you going to create a strong, member-led organization around something less immediate like climate change? Or changing school disciplinary policies to reduce the school-to-prison pipeline? Pick a progressive cause, it’s probably less material than people’s jobs.

Well that’s a bummer

I hate to leave on such a pessimistic note. I do think people are making valiant efforts to rebuild membership organizations and to do authentic organizing and they should keep plugging away. We’ll need to fill this hole of secular, atomized society one way or another and maybe the tides will turn. We need to keep experimenting with what hooks people to join these movements. But you can’t experiment and figure this out properly without an understanding of why things aren’t already working better.

When it comes to politics, the other idea I’m still noodling on is the role of aesthetics here. That’s what I plan to write about next.

In my first draft, I wrote former Angels pitcher Dylan Bundy. Apologies to all innings-eaters. These are the mistaken connections your brain makes when you’re too much of an infovore.