Creative Federalism: How Foundations Got Entangled with the American State

Part 2 of my series on Philanthropy, its history, and how to fix it

My first post on the history of American philanthropy was about the birth of the modern foundation. It looked at how figures like Carnegie and Rockefeller transformed giving from a personal, often religious obligation into a professionalized, institutional endeavor. We talked about the rise of general-purpose foundations, their sweeping ambitions (“the well-being of mankind”), and the early critiques that they looked an awful lot like unelected governments.

Because foundations didn’t just build Carnegie libraries or fund food banks, they were shaping society in more profound ways. In this post, I look at how foundations embedded themselves in the machinery of government—building fields like public administration, piloting anti-poverty programs, shaping policy frameworks, and eventually prompting Congress to draw new legal boundaries around their power.

During this period, American philanthropy never stayed in its lane because there wasn’t really a lane. The boundaries between “public” and “private” have always been squishy in American governance.

I definitely felt this tension working at a large health foundation. Over the years, that Foundation has partnered plenty with public agencies, funded plenty of advocacy efforts that influenced local and state politics.

That can sound shady if you’re feeling conspiratorial, but I think that very similar dynamics play out with government and the business community, especially large companies. Shocker: big stakeholders with lots of resources will inevitably be big players in public affairs, and philanthropy is one of the main avenues for that influence.

Most of this information came from Olivier Zunz’s excellent Philanthropy in America, which is especially sharp on the evolving relationship between the public sector and philanthropy. He traces foundations’ path from controversial novelty to essential governing partner and a powerful force in civil society during the 20th century.

Philanthropy helped create “Public Administration”

One of the biggest contributions came early in the history of the foundation. As Alasdair Roberts documents, Rockefeller money helped build the academic field of public administration. In the 1920s and ’30s, they supported graduate programs, research centers, and expert commissions that helped staff and build out the increasingly professionalized American bureaucracy. Rockefeller has a page about this work on its Archive website.

This is a crucial point, right at the dawn of the American administrative state. Essentially they were helping realize the vision of people like Woodrow Wilson, who (before being President) was a noted scholar and an advocate for a more professionalized field of public administration.

At a moment when the state was trying to scale up, Rockefeller philanthropy offered money, training, ideas, and infrastructure. Whether that’s capacity-building or soft influence depends on how you see it.

Blurred lines

In the decades that followed foundations stayed active but quiet and tactful. After early criticisms that foundations were overreaching or politically suspect, many large funders doubled down on a technocratic identity: supporting research, demonstration projects, and the institutional infrastructure of knowledge. Basically, applying Rockefeller’s approach to public administration towards other areas.

This was the era when big philanthropy moved heavily into higher education, the social sciences, public health, and international development. Foundations like Ford, Rockefeller, and Carnegie were central to the creation of new academic fields, from international/area studies to economics to urban planning. They invested in what you might call pre-political work: seeding the ideas, disciplines, and datasets that would later feed into policymaking.

In foreign policy, the boundaries between government and philanthropy were particularly blurry. Zunz notes that during the Cold War, foundation staff were often in close contact with the State Department, and not just socially. Think tanks, university programs, and international NGOs received foundation support to advance goals that often aligned the US government’s strategic interests. The lines between soft power, expertise, and foreign aid were never firm.

In domestic policy, foundations’ role jerked around a bit. During the Depression, Herbert Hoover encouraged private philanthropy to step up where the federal government couldn’t. But then FDR came in and reasserted the government’s dominance in solving social problems. He didn’t want public welfare outsourced to elite donors, however well-meaning. But even then, the infrastructure being built by foundations was hard to ignore.

Nevertheless, foundations played a crucial supporting role. Zunz points out that many nonprofits and public-private partnerships relied on foundation support to test out new models that might one day scale. Some of these became de facto policy labs. Others fizzled quietly. But the model was already in place: foundations funding work that the government watched, borrowed from, and occasionally absorbed.

By the time the 1960s rolled around, foundations were well-positioned to engage domestic policy. Not because they suddenly became more political, but because they’d already spent decades building the technocratic infrastructure that policy makers now turned to as they launched their War on Poverty.

Make Society Great Again

The Great Society was a turning point. Not just in public ambition, but in how government and philanthropy worked together. Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty expanded federal reach into health care, housing, education, and civil rights enforcement.

In doing so, it built on models that had already been seeded by foundations, especially Ford. The Ford Foundation had funded early experiments in community-based planning and poverty alleviation like the North Carolina Fund and Action for Boston Community Development. These programs prioritized local voices, decentralized control, and nonprofit partnerships. When the federal government needed models to scale up, they turned to what Ford and others had already piloted.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who worked inside both academia and government, once credited the Ford Foundation with helping invent “a new level of American government.” Suddenly, you had organizations all over like community action agencies, modeled after programs piloted by Ford. They’re quasi-public and operate with a mix of local, state, federal, and philanthropic dollars and have Boards that legally had to include community members.

If this sounds like it has a lot in common with some nonprofits in your city, you may be right. But in LBJ’s time this was a new model.

These agencies, and the Great Society era more broadly, embodied an approach that Zunz calls “creative federalism.” Foundations didn’t just complement government programs, they also helped design and staff them. This was a far cry from a charity model of philanthropy. While some philanthropists and foundations continued to focus on filling gaps, ambitious funders like Ford were deeply enmeshed with the government and were helping design and knit together the public safety net.

This period also saw philanthropy play an important role in civil rights and racial justice. Foundations funded litigation strategies, community organizing, and public awareness campaigns that helped lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. Philanthropy was also active in early funding and the eventual professionalization of the feminist movement, which Kristin Goss has written about.

The same dynamics are playing out today for whatever kind of movement you’re thinking of across the political spectrum.

Trying to draw clear boundaries

Unsurprisingly, this kind of tight-knit relationship between government and philanthropy, plus philanthropy’s role in broad social change and upheaval, triggered backlash. By the late ’60s, congressional hearings were grilling philanthropic leaders about their political leanings, their opaque processes, and their tax-exempt status. The sense was: if you want to shape public life, you should at least pay taxes like everyone else.

Eventually, Congress passed the 1969 Tax Reform Act. Among other things, it:

Legally separated public charities from private foundations

Public charities had broad donor bases and more public oversight, while private foundations were typically controlled by a single donor or family

Limited foundations’ ability to engage in direct political activity

The Act prohibited foundations from lobbying, engaging in electoral politics, or funding organizations that do. It allowed educational and charitable activity but imposed stricter restrictions on private foundations than on public charities.

Required annual payouts and more financial transparency.

Foundations were required to file detailed annual reports (Form 990-PF), list trustees, and disclose some information about grants and investments.

Overall, the idea was to draw a firmer line between private giving and public influence. But as anyone who’s worked in this space knows, the line stayed blurry.

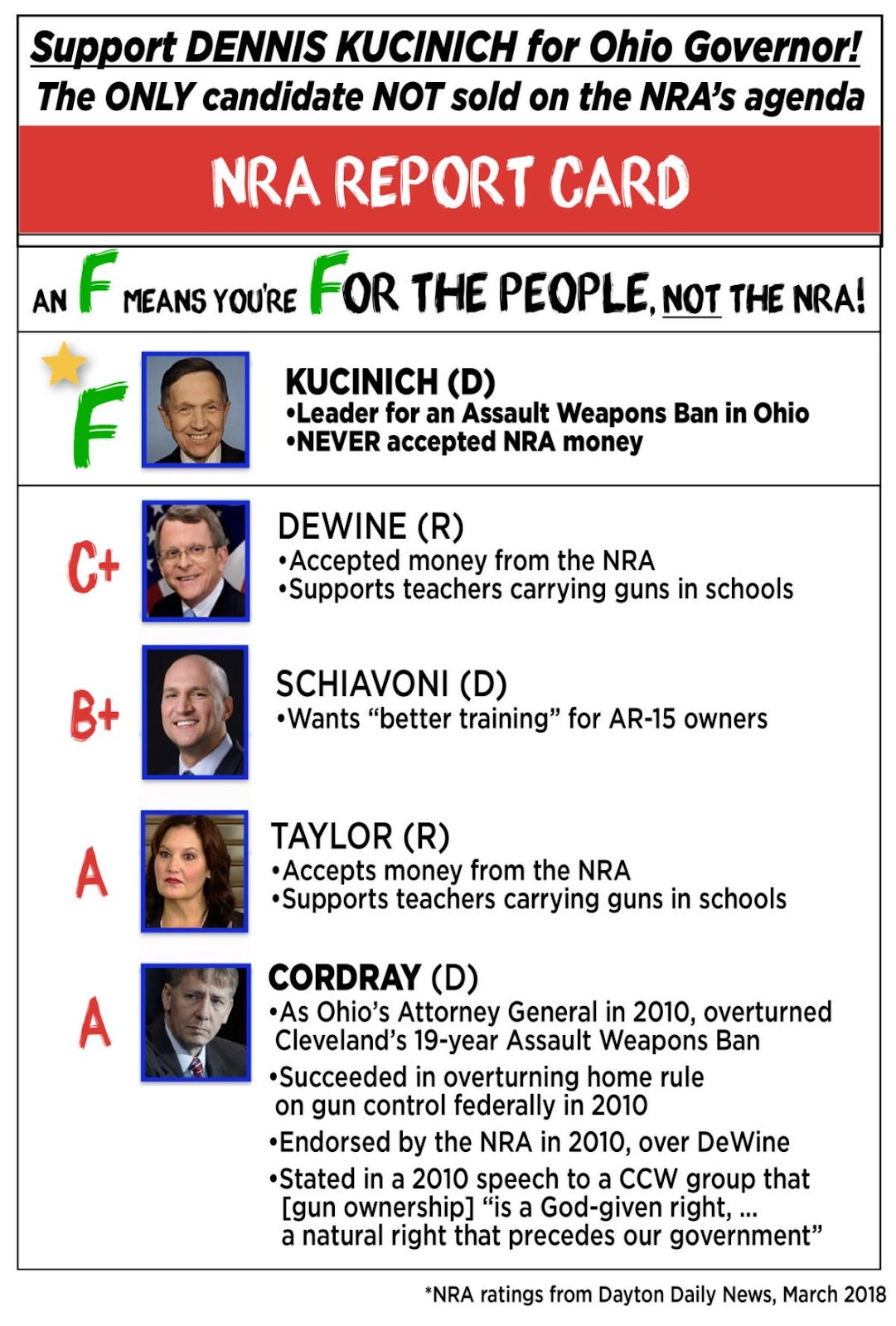

Foundations weren’t allowed to lobby. But they could fund research that ended up in the hands of lobbyists. They couldn’t support candidates, but they could evaluate policies, host convenings, and help support activities like publishing Report Cards to educate the public.

It’s not that foundations ever fully captured the state. But they were always in the room. Writing white papers. Designing pilot programs. Training bureaucrats. Sitting on commissions.

Political theorist Rob Reich has argued that philanthropy is best understood not as a private virtue, but as an “artifact of the state.” The 1969 reforms reflected exactly that tension: a state both enabling and wary of philanthropic power.

Jodi Sandfort has a nice framework for classifying the various roles that foundations and other nonprofits play in relation to the government. She describes three roles:

Complementary — delivering services alongside government

Example: A foundation partners with a city health department to expand access to mobile dental clinics for low income families.

Supplementary — focusing on unmet or emerging needs

Example: A foundation funds a pre-K pilot program in a city that doesn’t have any public pre-K. They hope to prove that it’s effective and spur eventual public investment.

Example: A religious foundation funds faith-based mentorship programs for people in prison. There’s no path for public funding for this because of the First Amendment, they’re just trying to do good.

Adversarial — prodding the government to make changes

Example: A foundation funds a legal advocacy group that sues the state over discriminatory housing policy or supports organizing efforts to push for Medicaid Expansion.

The trick is that most large foundations end up doing all three, often at once or with unclear boundaries. The lines can be particularly blurry when you’re funding direct services in the Complementary or Supplementary buckets. When are you displacing government funding vs. piloting a cool program that will spur it? As my first boss in philanthropy told me, it’s more art than science.

The line between public and private has always been porous in American governance, and philanthropy has danced around it. From staffing early bureaucracies to shaping major civil rights battles to designing community programs later scaled by the federal government, foundations have been both allies and irritants to the state. The post-1969 rules didn’t end the tension, they just formalized it.

It’s easy to critique this entanglement. Sometimes it’s deserved. But like I said in my last post, it’s just a smart play to try and influence the vast amount of public dollars that are spent every year. And this policy realm is where a lot of the most creative, risk-tolerant work happens. I’ve seen foundations fund important community-led work that the government wouldn’t touch, or work closely with politicians to roll out a cool public safety initiative that would take years to even start to pilot with the normal mechanisms of government.

But I keep circling this question: should this make us uncomfortable? To some extent, yes. Philanthropy needs to step up often because of a lack of state capacity. The government should be capable of nimbly piloting the kind of cool ideas that more and more often run through private philanthropy. See my review of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance for more info on that kind of state capacity discourse.

But also, as Rob Reich argues in Just Giving (which I will cover in my post in this series), there’s actually something paradoxically great about having completely un-accountable philanthropists insert themselves in a pluralist, liberal democracy. They can experiment and fill some crucial gaps that would still be there even in a hypothetical flourishing, high-state-capacity society.