The perils of misinforming ourselves

We need more honesty about guaranteed income studies

I’m taking a two week trip to Colombia with my girlfriend to celebrate her finishing law school and taking the Bar Exam. So I’ve got a shorter post this Monday, a follow up to my last two posts on GBI. Enjoy!

Shortly after my first post on the disappointing results from some recent guaranteed basic income (GBI) studies, two related items popped up in my feed that felt worth sharing.

First, NYT coverage of another GBI study (similar to the Open Research one on parenting) that found a null result:

After four years of payments, children whose parents received $333 a month from the experiment fared no better than similar children without that help, the study found. They were no more likely to develop language skills, avoid behavioral problems or developmental delays, demonstrate executive function or exhibit brain activity associated with cognitive development.

“I was very surprised — we were all very surprised,” said Greg J. Duncan, an economist at the University of California, Irvine and one of six researchers who led the study, called Baby’s First Years. “The money did not make a difference.”

I bring this up because it’s easy to dismiss the Open Research studies. I’ve read a number of social scientists say some version of “don’t base your opinions on single papers, look at the literature as a whole.” But there are some consistent null findings here that go beyond the one paper.

Poor summaries lead to bad reporting

The second item: a great Twitter thread from John Arnold about how researchers reported results from an Oakland GBI pilot. Arnold’s writing and the work of Arnold Ventures has been quite influential for me as I think through the need for strong, evidence-based policy.

The initial study here was about Oakland’s GBI pilot, which gave $500/month for 18 months to low income residents with children. Citing No Spin Evidence Review, Arnold highlights how the study’s abstract makes the pilot sound like a success. But in reality, there was no statistically significant impact on any of the outcomes that they committed to measuring at the end of the 24-month study.

This is part of why I’m a fan of Open Research’s studies and rely on them so heavily in my first post on GBI. I’m inclined to trust people who honestly report null findings, including ones that may be inconvenient to them. You don’t think the Open Research crew would love to find big positive impacts? They invested $60M!

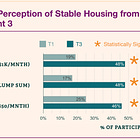

Unfortunately, this case tracks with what I found as I looked into the results of recent GBI studies. As I noted, Denver’s GBI pilot to reduce homelessness found, essentially, that it did not make a difference. People who received the money ($12,000 spread out throughout the year) found stable housing, but at the exact same rate as people who didn’t get the money.

But go to their “Research” page and this is the first bulletpoint:

That is… true. But that omits the fact that the $50/month payment group was intended to be the control group, as in the group that should experience no effect. Or at least less of an effect, if money was the real mechanism for change here.

Media coverage has been equally misleading. Here’s the first bit of CNN coverage from the Denver Basic Income Project’s Media page, which switches gears part way through and casts any opponents of GBI as Project 2025-supported haters:

Dylan Matthews, a noted fan of cash transfers (especially globally), noted this type of misleading coverage about a year ago at Vox. Part of the issue here is that it makes it hard to understand why anyone would be opposed. This Axios article, which covers the Denver City Council’s refusal to continue the project, doesn’t report the null finding at all.

Ultimately, I blame the researchers here, who seem to have too vested an interest in advocating for this policy (regardless of outcomes). This is obviously the case for Denver Basic Income Project, which was hosting rallies to try and keep the expanded pilot in the city budget and posted about it on social media. Journalists aren’t well-equipped to dig deep into research methodology and, because of education polarization, are also going to generally skew progressive and uncritically sympathetic.

Weak studies muddy the literature

Part of the reason that I’m skeptical of relying on qualitative evidence is that if people can tell themselves stories to explain away bad quantitative findings, I have no faith that they will not just tell whatever stories they want to with qualitative findings.

But it’s easier to pump out qualitative stories and weaker studies. In addition to leading to a lot of misleading reporting, this also cumulatively leads to a misleading literature that’s harder and harder to sort through.

Sometimes I try to sanity check myself and my sense of research literature with GPT. I did a Deep Research report, which went through a number of pilots and summarized it as follows:

The recent wave of guaranteed basic income pilots in the United States has provided a rich body of evidence on the economic and social impacts of direct cash assistance. Across diverse locations and populations, the results have been strikingly consistent in demonstrating positive outcomes: recipients tend to use the money wisely for essential needs, they gain greater financial stability (paying down debt, saving a bit, handling emergencies), and they experience improvements in well-being – from mental health and stress relief to better housing and opportunities for their children. Crucially, the data dispel common fears: there is no evidence of people en masse quitting jobs or misusing the funds on vices. In fact, some pilots saw employment increase and community life strengthen when people were given a basic income floor.

It is important to note that these pilots remain relatively short-term and small-scale compared to a permanent, nationwide program. Yet, they offer a proof of concept that echoes findings from past income experiments and global research: cash support, given with trust and minimal conditions, can uplift individuals and families out of poverty’s trapurban.orgurban.org. We have seen families in Mississippi emerge from crushing debt, residents in California start businesses or move to safer homes, and parents in New York and Illinois finally exhale knowing they can put food on the table. As one Urban Institute analysis concluded, “historic and current guaranteed income experiments demonstrate excellent outcomes for children, and strong gains in adult mental health, physical health, and parenting, as well as large increases in food security and housing stability.”

With dozens of pilot evaluations now either completed or underway, policymakers are gaining a clearer picture of what a guaranteed income might achieve. The findings from the last 5–7 years are informing proposals at city, state, and even federal levels (such as bills to create state GI funds or expand the Child Tax Credit as a form of basic income). The conversation is shifting from “Will people work or waste the money?” to “How can we effectively implement and scale up these proven benefits?” The collective lessons from Stockton, Hudson, Chicago, and beyond suggest that a guaranteed basic income, as a complement to other social supports, is a powerful tool to improve economic security and family well-being. In summary, the pilots have demonstrated that when people are given a modest but steady financial foundation, they not only stay afloat – they tend to climb upward, bringing their families and communities with them.

But all it took was one question to pull at this a bit. I said “My sense from high quality RCT-type studies (see: OpenResearch's work on this, NBER papers they've published) is that there are actually a lot of null findings here, especially for social outcomes. Is that wrong?”

Here’s an abridged version of what I got back, much more measured:

Short answer: you’re not wrong. If you narrow to the highest‑powered, preregistered RCTs (esp. the OpenResearch/Y Combinator project and the Compton Pledge RCT published as NBER papers), you see a lot of small or null average effects on most social outcomes, and pretty muted labor-market effects too. The consistent, statistically clear wins tend to be food security, the ability to cover emergencies, and reduced financial volatility. Big, durable gains in mental health, physical health, or children’s outcomes are mostly absent or short‑lived / concentrated in subgroups.

[Summarized a few of those studies…]

Why the “pilots are great!” narrative exists: Many city pilots (Stockton SEED, BIG:LEAP LA, etc.) either weren’t RCTs, were underpowered for many secondary outcomes, or emphasized descriptive / self‑reported well-being gains that look big but don’t always clear stringent statistical thresholds. Stockton’s employment bump (12pp vs. 5pp in control) is real, but that study wasn’t the same kind of large, preregistered, multi-year RCT as OpenResearch’s. LA’s BIG:LEAP did report “overwhelmingly positive” results, but most were self‑reported and short-run, and we don’t yet have an NBER-style deep dive to line them up directly against the OpenResearch findings.

So, the synthesis:

Robust, RCT-grade evidence: modest labor-supply reductions (or near-zero effects), clear but limited financial-stability gains, lots of nulls on broader social/health outcomes, and heterogeneity that favors the most distressed subgroups. NBERNBERNBER

Program-run / quasi-experimental pilots: more upbeat stories on mental health, employment, family well-being — but methods, time horizons, and multiple-comparisons discipline differ, so you can’t read them as contradicting the RCTs so much as painting a friendlier descriptive picture.

Takeaway for policy skeptics and fans alike: guaranteed income reliably buys stability (food, bills, debt), doesn’t tank work, and doesn’t magically transform everything else. If you’re hoping for large, durable average gains in health, cognition, or long-run mobility from transfers of this size/duration, the best current RCT evidence says: temper expectations.

In addition to showing that we should be careful relying on GPT as a research assistant, there are some broader takeaways.

We need scholars who honestly and impassionately report results and marry the qualitative with falsifiable, quantitative outcomes. The media needs to be a bit more critical. Otherwise we’re liable to fall victim to our own misinformation, over-commit and over-promise with these kinds of programs, and then suffer the backlash when they work exactly as the studies told us they would.