As I wrote about recently, I’m both a recovering coastal elite and a recovering Marxist. Part of what’s appealing about Marxism is that it is essentially a religion. It’s a totalizing way of looking at the world in grand structural terms. There are good guys and bad guys, there’s a “right” direction to history.

My break-up with Marxism

Much like I describe myself in this blog as a “recovering Coastal Elite,” I often refer to myself as a “recovering” or “former” Marxist. In progressive spaces, it’s usually social currency to be the most radical person in the room, so my colleagues are often surprised.

So when my faith in that worldview began to crack, I naturally began to look for different answers to the same Big Questions: justice, the proper role of the state. My work in the real world was demonstrating the immense complexity of social problems and the systems around them, but I still felt like it was a cop out to just be focused on tinkering at the margins.

After all, in the Marxist universe, the people who focus on that are the dreaded Reformists, who always get second shrift in historical narratives next to the Cool, Radical Revolutionaries. People like Emma Goldman, Rosa Luxembourg, or Leon Trotsky. Reformists were sell-outs.

It wasn’t until I read Charles Lindblom’s “The Science of ‘Muddling Through,’” a classic in political science, that I encountered someone who provided a solid, theoretical justification for being just that. A reformist. An incrementalist, in his wording. Tracing this idea led me to pragmatism, America’s first major philosophical school. I’d heard a lot about how John Dewey, one of the main figures in that school, is dry and hard to read. But why not give it a shot? I checked out The Public and Its Problems.

Getting Over Old Questions

Dewey wants to invert the common philosophical approach of reasoning about theoretical Absolute Truths and Big Causal Forces and then looking at the real world to see whether it aligns. Without naming names, he basically says that the State represents different Absolute concepts for all sorts of philosophers, including Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Kant, and Hegel. They all stroked their chin and thought about what the one, “right” form of state is and reached different conclusions.

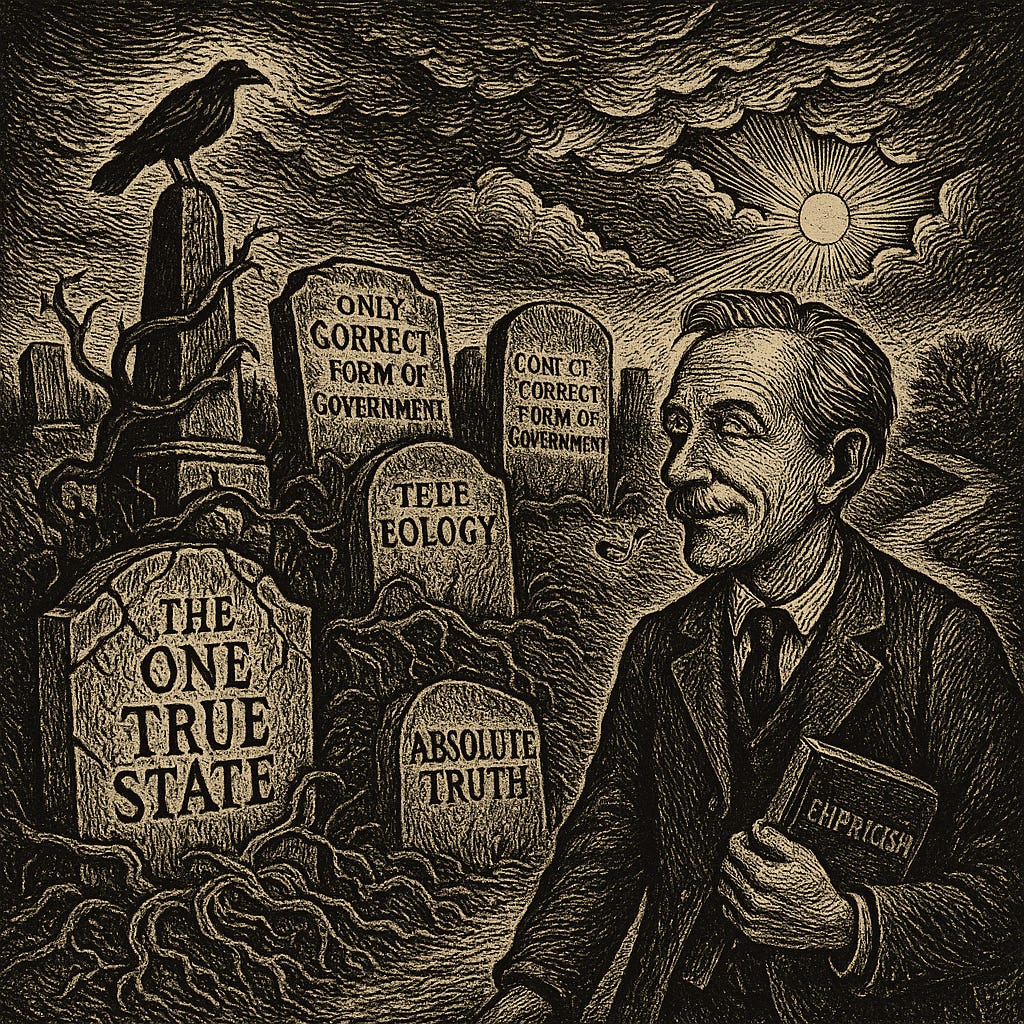

In fact, we’ve made no real progress on the issue since Ancient Greece… so maybe we should revisit the method? I like the way he puts it in another essay, “The Influence of Darwin on Philosophy:”

Old ideas give way slowly; for they are more than abstract logical forms and categories. They are habits, predispositions, deeply engrained attitudes of aversion and preference. Moreover, the conviction persists… that all the questions that the human mind has asked are questions that can be answered in terms of the alternatives that the questions themselves present. But in fact intellectual progress usually occurs through sheer abandonment of questions together with both of the alternatives they assume— an abandonment that results from their decreasing vitality and a change of urgent interest. We do not solve them: we get over them.

So let’s get over the obsession with the one “correct” form of the State. Instead, Dewey thinks that philosophers should carefully observe the world and then develop models about how it works. Essentially, he wants philosophy to evolve into what we’d now call social science, grounded in empiricism. Of course, this opens up a whole suite of empirical questions: what to measure, what to value, how to handle quantitative versus qualitative evidence. But I’ll leave that to the side for now.

I’m quite sympathetic to this argument. And Dewey’s not as terrible a writer as everyone says! The book is dry, sure, but there’s much more obscure political theory and philosophy out there. The man has a gift for metaphor and clearly re-states and summarizes his own arguments to help you follow along.

His most annoying academic habit is arguing against people without mentioning them. Lots of allusions, which may work for an erudite academic philosophy crowd, but it’s relatively obscure for those who don’t immediately know when he’s referring to Kant or Hegel or Aristotle. But the upshot is that those thinkers were asking the wrong questions anyway, so it’s fine to miss the finer points of his allusions.

Post-Truth Politics

There’s another consequence of Dewey throwing aside the idea of Absolute Truth and cosmically-ordained goals that all societies should strive for. We, or “The Public,” need to work these questions out for ourselves. This is post-Truth politics. But not in the “alternative facts” sense. More a recognition that in a modern democratic society there’s no Church or King to tell us what to do and what to prioritize. It’s up to us.

And when we’re talking about tradeoffs between two good things (e.g., efficiency and fairness) where there is no right answer, the closest thing we have to a “right” answer is “how does The Public want to balance these issues?” Democracy, ideally, is the process by which we surface and negotiate over Public values. Then we do our best to translate them into reality, track the results, and adjust as needed. Dewey calls this an “experimentalist” approach to politics.

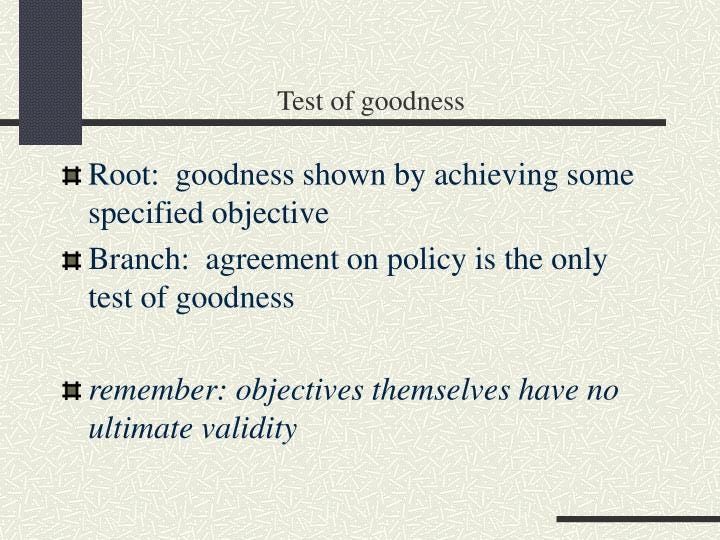

This is where I began to feel a parallel with the Charles Lindblom article I mentioned at the top. The central metaphor that he uses relates to trees. Many believe that policymaking should proceed via the “root” method, starting from fundamental goals and values (“the roots”) and then logically tracing your way to every policy that should follow (“the branches”). Marxism works that way: the ideal society should be organized in a particular way, so how do we work towards that end state?

Lindblom starts by examining real, existing policymakers in modern democracies and finds that this isn’t how they approach their work at all. Instead, they follow an incrementalist “branch” method. Taking the existing tree shape as a given, policymakers tinker with policies at the current margins. In fact, they hardly think about the roots, those Big Questions about the “right way” to organize society. It’s not that incrementalist policymakers are struggling with or failing to answer those huge, comprehensive political philosophy questions. In Dewey’s words, they’ve just gotten over them.

It’s not an exact match, but Lindblom and Dewey arrive at pretty similar conclusions about how to pursue an ideal society. Focus less on Absolute Truths, more on the problems directly in front of us and attainable solutions. Lindblom terms his approach incrementalism, while Dewey likes the term “experimentalism.” Like Dewey, Lindblom thinks that the ultimate test of whether a policy is “good” is not whether it conforms to some larger Absolute theory, but whether it is agreeable to the members of a democratic society.

That being said, I’m not sure if Dewey would embrace the Incrementalist label. At various points in The Public he does acknowledge that political structures and institutions can become so out of sync with the needs of their people that revolution becomes necessary. But Lindblom never says that revolution is unnecessary. His work is just acknowledging how policymakers behave in the real world and defending them from academics who see the “root” method as the way things should always be done.

To sum it up, both thinkers stress the need for marginal thinking and tinkering, taking the current status quo as our starting point. They also advocate for constantly evaluating our policy work and being open to pivot if the consequences of a given intervention differ from expectations, or if the Public’s desires change.

My Takeaways

Overall, Dewey is a helpful piece of the puzzle for me as I chart the course for my own politics and make sense of the kind of social impact work that I do. The experimental attitude jibes well with the kind of epistemic humility that has been drilled into me by studying the complexity of social change. It is just really hard to predict the consequences of even small policy changes and we should all be prepared to be proved wrong and adjust.

I also think that the whole idea of “just ask different questions” is an intriguing solution to another problem I have. It’s common now for conservatives to rail against modern academia and its fancy postmodern theory. People like Foucault. The upshot is that there is no Absolute Truth and everything is relative and socially constructed. Right wing critics are correct that this is a pretty unsatisfying conclusion and it makes it hard to get people excited and motivated to live fulfilling lives.

But the problem to me is… they’re right? It’s like my issue with religion. On paper, it’s an incredibly important social technology that evolved over millennia to address many important human needs for meaning, community, structure, you name it. I was raised in a religious community and would love to continue to be involved. The only problem for me is that… God isn’t real. And yes, I’ve tried re-defining God in pantheistic terms and other workarounds, but it’s just not the same for me. It’s really hard to motivate yourself to keep up with religion’s nourishing rituals and community when the underlying cosmic driver for it all is gone.

Perhaps what is most valuable about Dewey for me is that he still finds meaning while acknowledging the absence of Absolute Truth. He offers a compelling vision of a socially constructed world, but it’s not as pessimistic and cynical as the French postmodern philosopher worldview. There’s something beautiful about the meaning coming from the democratic process of humbly trying to improve the world in collaboration with other humans. As I’ll write about in a future post, my worry is that Dewey’s vision for a robust, deliberative democratic society has not exactly panned out in the ensuing decades. But it’s at least worth striving for.

Interesting piece, Ben. Like you, I appreciate Dewey’s pragmatic approach. Do good for its own sake, because it makes the world a better place. And it makes you happier, too. That is enough of a motivation for me.

Thanks for an interesting piece. One thing I find appealing about incrementalism as you describe it, is that it is the attitude most compatible with the prioritization of human life and welfare (even if misery abounds in society as you find it). The reason being that all alternatives (the "from the roots" approach, per your article) make the ideal society so desirable, so mystically superior, that any amount of coercion or violence is warranted to reach the goal (Marx's sinister breaking-eggs-to-make-omelettes metaphor). All revolutions produce untold misery and immense mass graves. Hence, any societal reorganization that demands a revolution is highly suspect - if you care about human life.