Ultimately, the reason that I read Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland is that it feels to me like we’re living through a similar cultural and political moment right now. I read history in part because it comforts me to know that everything has happened before. It calms me down in seemingly-unprecedented times.

As a reminder, Perlstein’s main argument is essentially that Richard Nixon created the modern culture wars that still define American politics. The book was written in 2008, but at many times feels like if you blocked out the proper nouns it could be talking about Trump and American politics from 2016-2024.

I’ve written three posts: one giving an overview of Nixon himself, two diving into the political and cultural issues that Nixon harnessed to win political power, and three taking a detour into Philip Roth’s American Pastoral to explore how it felt to live through this era and its divides. In this last post I wanted to fully explore the connections between this book and current politics.

Overall, some of the conflicts Nixon exploited still define American politics, but others have shifted in ways that complicate the comparison. It’s tempting to see everything through the Nixonland lens, but not all culture wars are the same. Some battles have been won, others have evolved, and new ones have taken their place. The challenge is figuring out which lessons still apply.

Are these really the same culture wars?

Perlstein, writing in 2008, argues mostly persuasively that Nixon was instrumental in setting up the modern form of political polarization we see today, particularly with respect to culture wars. But I think it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Some of that is definitely true: anti-elite, populist politics are certainly having a moment. On the other hand, the specific cultural issues at play today are totally different than they were even 20 years ago and progressives won many of the old battles.

In the Nixon era, there was a lot of controversy over teaching sexual education in schools. Perlstein quotes one grumpy parent who hilariously says “My wife and I have never discussed sex in seventeen years of marriage.” Basically everyone takes sex ed today.

Republicans are about to appoint Scott Bessant as an openly gay Treasury Secretary. In the Clinton years, James C. Hormel was opposed for being gay for the relatively-insignificant post of Ambassador to Luxembourg. And appointing an openly gay person to even that kind of post would have been unthinkable in the Nixon era, perhaps a sign of crazy free love hippie excess.

But it also feels like right wing cultural backlash politics are back. As some say, there’s been a “vibe shift,” or a pendulum swing to the right culturally. How to make sense of this? Matt Yglesias touches on some of this ambiguity in a recent piece:

I remember the week after the election, a gay college student told me that some of his friends were concerned that Trump’s win would threaten the Obergefell decision and marriage equality. I don’t really know what Trump is going to do, but I would be genuinely shocked if that happened. A big part of the “rightward” shift in vibes is not the revivification of old conservative ideas but precisely the opposite. The movement for LGBT rights gets weaker if most people decide that L, G, and B are no longer up for debate. …

In a Barnes & Noble in Williamsburg, Virginia over the weekend, I saw three different books about how the Christian Right is taking over America. I don’t think that newly MAGA-pilled tech executives or newly MAGA-pilled teenagers are backing Trump in order to facilitate a Christian Right takeover. I think they are backing him because they don’t see that as the stakes in American politics.

It’s really hard to assess the arc of cultural issues in the moment. In 1972 it probably felt like the world was ending and 60’s progressives were hosed. But flash forward to 2025 and schools have sex ed classes, gay people can get married, mainstream feminists of Nixon’s era lost some issues like the Equal Rights Amendment but also pretty clearly won on fundamental issues like “should women be working?”

To pick one current example: In 50 years is the Trump anti-trans backlash going to feel like a momentary backslide? Or is it actually setting back the civil rights of that group of Americans back by decades? Honestly, who knows.

Extremism is bad and helps the other side

The book was a potent reminder for me about how much political extremism on the left and right are mutually reinforcing. Here’s one example:

[LBJ] had staked his political future on a nation’s sympathy with the black freedom movement.. But the black freedom movement was now defined by language like this, from a leaked SNCC position paper: “When we view the masses of white people..we view in reality 180 million racists.”

Sometimes being impractically extreme was literally a part of left wing activists’ theory of change, as in this case of black militants at Cornell:

The militants had embraced a revolutionary dialectic. Escalating demands, impossible to meet, served “the objective of raising the level of awareness among blacks” to that of the vanguard, which would come to share with the vanguard “another objective, the destruction of the university—if not its complete destruction, at least its disruption.” Issue unreasonable demands, and “the beast we are dealing with will use all the means at his disposal to maintain control of power.” That would reveal the fascism behind the liberal facade.”

These sort of protests tend to get viewed with rose-colored glasses, with the worst parts of it being stripped away and the idealism remaining. But the more I read the specifics of them, the less sympathetic I felt. And think about how you’d feel if you were a parent and found out that these were the speakers your kids were seeing at college:

Jerry Rubin was on a speaking tour. On April 10, 1970, he said, “The first part of the Yippie program is to kill your parents. And I mean that quite literally, because until you’re prepared to kill your parents, you’re not ready to change this country. Our parents are our first oppressors.” His audience was fifteen hundred students at the relatively quiet campus of Kent State University in Ohio.

This is the kind of thing that made people go “well if that’s what the protestors at Kent State were listening to and platforming, maybe it’s not the National Guard’s fault..” That is also the wrong position to hold, but don’t give people any more reason to sympathize with stupid positions!

The revolutionary dialectic people are kind of right. If your only goal is total revolution, having things get better probably doesn’t help you to your goal. But the revolutionary track record seems pretty poor, so I’m happy to just make things better for people.

Guilting people isn’t a great theory of change

I want to bring a quote from my second post in this series back about the Kerner Commission:

The President [LBJ] was aghast at the Kerner Commission report. It did the one thing he’d been so careful never to do when laying the political groundwork for his sweeping social and civil rights legislation: blame the majority, instead of appealing to their better angels. None wanted to be hectored as oppressors. They thought they had enough problems of their own.

I do think the same theory of change and messaging that concerned LBJ here has been on display in lots of progressive anti-racist circles in recent years. The theory of change: if we call everyone racist and white supremacist, they’ll surely want to help. But that doesn’t actually work.

If racial hierarchy and power operate as they say it does, then educating white people about that fact would actually make them want to help even less. Either because they resent being called oppressors (see above) or because they go “wait, you’re saying I benefit from this system… but I should want to dismantle it?” I don’t think that part always operates consciously, but I believe it does subconsciously.

And, as we saw in an election when racial minorities swung towards Trump, it doesn’t even really work to pick up the votes of the people you think you’re helping with this strategy.

Better to adopt positive sum framings. Heather McGhee’s The Sum of Us is a good recent book about how racism hurts everyone and that we should try to organize people around that fact instead of running around telling white people that racism is great for them but they should also totally try to end it.

Gaza is not Vietnam, Iraq is

When I mentioned to friends that I was reading this book in part for its modern parallels, a lot of people said “ah yeah, Gaza is really dividing the Democrats like Vietnam did in 1968.” I get the connection, but I think it’s a misread. The real equivalent today is the Iraq War and other associated War on Terror government activity.

When people write a history book in 40 years like Nixonland today, it’s easy to envision an Iraq War throughline. I’m borrowing a point from Matt Yglesias (though I’ve also seen others make it on Twitter), but basically here’s one way to tell the last 20 years of American politics (my paraphase):

The Iraq War helped give the 2004 election to Bush, because the Iraq War was still broadly popular,

It also helped give Obama an opening in the 2008 Democratic primary and the unpopularity of Iraq and George W. Bush helped Democrats win the national election,

The Bernie Moment in the 2016 Democratic primary is downstream of Iraq (and Occupy, but I don’t know that the anti-Hillary sentiment gains as much steam without her Iraq support and subsequent time as Secretary of State). This creates the shape of Democratic infighting for the next 8+ years, as Bernie brings power to a new progressive wing,

Breaking with the Republican Party line on Iraq is a huge part of what gives Trump his initial momentum in the 2016 primary, particularly by kneecapping the “favorite” Jeb Bush.

At a macro level, the Iraq War is a broadly-discrediting event for the elite political class in both parties that undermines public trust. It opens the door for anti-elite, populist sentiment across the political spectrum (e.g., Bernie, Trump). To me, Vietnam feels like an early and acute example of the dam breaking and the public seeing that the “best and brightest” aren’t all they’re cracked up to be.

As Martin Gurri argues, technology changes have made it continuously harder for elites to keep a lid on these kinds of failures. See my recent post about Martin Gurri’s theory of the recent rise of populist politics for more on this.

With respect to Gaza protests, I also think it’s easy to overestimate the impact that they had in 2024. Compare the 1968 DNC protests and the crackdown to the paltry turnout for the 2024 DNC, despite all the hype that it’d be a repeat of 1968 in the same city. That being said, it’s not like nothing in the book made me think of Gaza. Perlstein at one point describes the impact of Vietnam on the Great Society coalition as follows: “people who agreed about 98 percent of everything else were throwing schoolyard taunts at one another.”

Don’t feed the trolls!

Trump is so stylistically wild and unpredictable that it’s easy to lose sight of how old some of his tricks are. He shares with Nixon a knack for getting the right people to attack him. Trump does this from the stance of a disinhibited elite railing against the other elites and making edgy statements, while Nixon has more of an Everyman flavor. Here’s Perlstein on the “Nixon method”:

You didn’t have to attack to attack. Better, much better, to give something to the mark: make him feel like he has one up on you. Let him pounce on your “mistake.” That makes him look unduly aggressive. Then you sprang the trap, garnering the pity by making the enemy look like a self-righteous and hyperintellectual enemy of common sense. You attacked jujitsu-style, positioning yourself as the attacked, inspiring a sort of protective love among voters whose wounded resentments grow alongside your performance of being wounded. Your enemies appear only to have died of their own hand. Which makes you stronger.

Nixon perfected this method early in his career with the famous Checkers Speech. It’s a long story, but essentially Nixon is running as Eisenhower’s VP and there’s a financial scandal that would probably seem benign today (he has a rich donor who reimburses him for some expenses). Eisenhower’s considering dropping Nixon from the ticket. In response, Nixon gives one of the most famous American political speeches. He airs out all of his personal finances in a way that’s pretty embarrassing, because he’s not exactly rich. Here’s the kicker that gives the speech its name:

One other thing I probably should tell you, because if I don't they'll probably be saying this about me, too. We did get something, a gift, after the election. A man down in Texas heard Pat on the radio mention the fact that our two youngsters would like to have a dog. And believe it or not, the day before we left on this campaign trip we got a message from Union Station in Baltimore, saying they had a package for us. We went down to get it. You know what it was? It was a little cocker spaniel dog, in a crate that he had sent all the way from Texas, black and white, spotted, and our little girl Tricia, the six year old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids, like all kids, love the dog, and I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we're gonna keep it.

This is Nixon at his best and it saves his spot on the ticket and thus the rest of his career. Here’s how his fans saw it:

They interpreted the puppy story just as Nixon intended it: as a jab at a bunch of bastards who were piling on, kicking a man when he was down, a regular guy, just because they could do it and he couldn’t fight back. What will they dream up to throw at me next? To take away my little girl’s puppy dog? They, too, had mortgages, just like Richard Nixon. They, too, had cars that were not quite as nice as they might have liked–not nice enough to impress the neighbors, certainly. They, too, had worked hard as he had, their hard work not always noticed, sometimes disparaged. The agony of having to grovel to justify oneself just to keep one’s job: they had been there, too.

Again, Nixon and Trump have very different personal brands and styles. But I think the fundamental trick, getting the “right people” (liberal elites) to attack you and then playing the victim, is a shared shtick.

This playbook, particularly getting people to attack you for non-policy reasons, is employed by other outrageous populists around the world. It reminds me of a Luigi Zingales NYT article from November 2016, right after Trump was elected, attempting to share lessons from Italy’s experience with Silvio Berlusconi. It’s an incredibly prescient piece and honestly kind of tough to read after Trump’s return to power:

Now that Mr. Trump has been elected president, the Berlusconi parallel could offer an important lesson in how to avoid transforming a razor-thin victory into a two-decade affair. If you think presidential term limits and Mr. Trump’s age could save the country from that fate, think again. His tenure could easily turn into a Trump dynasty.

Mr. Berlusconi was able to govern Italy for as long as he did mostly thanks to the incompetence of his opposition. It was so rabidly obsessed with his personality that any substantive political debate disappeared; it focused only on personal attacks, the effect of which was to increase Mr. Berlusconi’s popularity. His secret was an ability to set off a Pavlovian reaction among his leftist opponents, which engendered instantaneous sympathy in most moderate voters. Mr. Trump is no different.

We saw this dynamic during the presidential campaign. Hillary Clinton was so focused on explaining how bad Mr. Trump was that she too often didn’t promote her own ideas, to make the positive case for voting for her. The news media was so intent on ridiculing Mr. Trump’s behavior that it ended up providing him with free advertising.

Constant attacks against someone of a more personal nature (rather than saying “he wants to cut taxes for rich people”) tend to wear on the public, especially those who are less politically engaged. It’s not like the public is attacking Trump for having a cute puppy named Checkers, but it’s possible that it lands the same way with voters.

Is the worst yet to come?

So was the Trump 2024 election the same as the Nixon 1972 49-state landslide? Definitely not. But as Ezra Klein recently wrote, the narrow popular vote win under-plays the “vibe shift” towards the right that’s happened.

Interestingly, Nixon’s 1972 landslide came during an election when Republicans didn’t even win the House. Similarly, Trump won, but MAGA governors and Senate candidates keep losing winnable races and his House majority could barely be smaller.

Overall, I have ambiguous feelings about the Nixon-Trump comparison. On the one hand, it’s a testament to the power of American institutions that the White House and country survived Nixon, a deeply paranoid President who directly weaponized law enforcement and other government tools against his enemies in a way that Trump has only gestured at thus far.

In the end, Nixon was impeached and forced to resign. My take away from listening to the season of Slate’s Slow Burn podcast about Watergate is that it took much longer for the Republican party to flip on Nixon than you’d think. Prominent Republicans like Reagan, George HW Bush, and others mounted incredibly impassioned defenses of him up until basically right before the moment that they flipped on him. Many of the details of the Watergate break-ins and the likely connections to the President were even known during the 1972 election!

American institutions and civil society were quite resilient and powerful during the Nixon era and the first Trump term. Politically, the ship has obviously sailed on Republican elites supporting a Trump impeachment like they eventually did for Watergate. They had the opportunity to bar him from electoral politics with the post-January 6 impeachment and didn’t. His support from the base is just too strong and civic leadership is just too weak.

This unfortunately leaves us in a scenario where we’re still quite vulnerable to norm erosion. There isn’t the backstop or breaking point that there once was. That lack of constraint, plus Trump’s incredible volatility, makes everything feel extremely contingent to me.

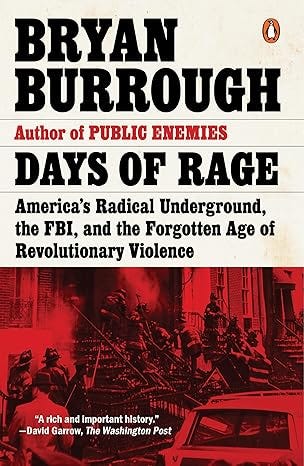

Another unfortunate lesson from this and other reading is that the worst may be yet to come, even after Trump’s final term ends. I recently read Days of Rage, a thorough account of left-wing terrorist groups like the Weather Underground and Black Panthers. The surprising thing is that most of the worst left wing violence didn’t even happen in the late 1960s when the left-wing counterculture was at its peak:

As one New Yorker sniffed to the New York Post after an FALN attack in 1977, “Oh, another bombing? Who is it this time?” It’s a difficult attitude to comprehend in a post-9/11 world, when even the smallest pipe bomb draws the attention of hundreds of federal agents and journalists.

“People have completely forgotten that in 1972 we had over nineteen hundred domestic bombings in the United States,” notes a retired FBI agent, Max Noel. “People don’t want to listen to that. They can’t believe it. One bombing now and everyone gets excited. In 1972? It was every day. Buildings getting bombed, policemen getting killed. It was commonplace.”

There are crucial distinctions, however, between public attitudes towards bombings during the 1970s and those today. In the past twenty-five years terrorist bombs have claimed thousands of American lives, over three thousand on 9/11 alone. Bombings today often means someone dies. The underground bombings of the 1970s were far more widespread and far less lethal. During an eighteen-month period in 1971 and 1972, the FBI reported more than 2,500 bombings on U.S. soil, nearly 5 a day. Yet less than 1 percent of the 1970s-era bombings led to a fatality; the single deadliest radical-underground attack of the decade killed four people. Most bombings were followed by communiqués denouncing some aspect of the American condition; bombs basically functioned as exploding press releases. The sheer number of attacks led to a grudging public resignation. Unless someone was killed, press accounts rarely carried any expression of outrage. In fact, as hard as it may be to comprehend today, there was a moment during the early 1970s when bombings were viewed by many Americans as a semilegitimate means of protest. In the minds of others, they amounted to little more than a public nuisance.

This returns us to the theme of extremes being mutually reinforcing. Andrew Sullivan, who’s as anti-woke and anti-Trump as they come, has been saying this for years to his anti-woke compatriots: nothing will energize left wing extremism more than another Trump Presidency. So far, it feels like people are worn out and there’s less capital-R Resistance going on, but perhaps the worst excesses of left-wing radicals are yet to come. And as Perlstein’s book showed, in the 60s and 70s there was plenty of right wing extremist violence that came along with it.

This is... scary. Imagine the frequency of 1970s violence with 2020s technology, plus a President who’s set a standard of pardoning right-wing political violence after January 6. But maybe we’ve just been living in an unusually peaceful time. I read Alan Taylor’s survey history of 1783-1850 (American Republics, all his books are great) and America used to be insane and chaotic and violent, all before we had an actual Civil War. So maybe we’re unfortunately regressing to a more violent mean.

One nit, then a real comment.

Nit: Nixon was not impeached—he resigned before that could happen, having been informed by Congressional leaders that the votes were there for both impeachment and conviction. I don't think this distinction matters much, and I personally count Nixon's resignation as the only success so far for the impeachment/removal process.

Comment on what the Nixon administration felt like: I was 11 when he was inaugurated and 17 when he resigned: he was was the first president I experienced as a politically-aware adult. It felt not so much like the end of the world as a know malevolent sleazebag being president. Congress was still in the hands of Democratic majorities, and the loss of the Senate under Reagan *did* feel like the beginning of the end.

Your account doesn't touch on the draft, which loomed very large in the social divisions. Before the institution of a draft lottery in 1969, conscription followed a procedure that reflected social status, but the supposed fairness of the lottery did not improve sentiment among the youth most affected. Conscription ended in 1973, two years before the actual end of hostilities. The draft formed part of a serious generational divide: The WWII generation experienced near-universal service among young men, and it was regarded as a patriotic duty. The much smaller numbers of combatants required for the Vietnam war meant the experience was never going to be universal, but the older generation generally didn't factor in the capriciousness of fighting a far-from-total war.

Back to Nixon: he could be taken down, and was, but you (following Perlstein, I guess) point out that in retrospect he was merely the beginning of a series of disastrous Republican presidents: Nixon, Reagan, G.W. Bush, Trump. Nixon did not attack expertise to the extent that Reagan did, but he *did* attack political opponents via dirty tricks. His used of the IRS to get at enemies (of which he had a famous list) looks like nothing compared to the current crowd, but it was seen as bottomlessly vile at the time, and there were Republicans in Congress willing to vote that way.